A recent theory that I find unconvincing. But it does not relate the the formation of placer gold deposits. it relates to the source of the gold that then formed the gold-quartz veins in bedrock. So no relevance to placer (alluvial) gold that you prospect for - i.e. they would agree with me on that, it is not contentious..yella fella said:

-

Please join our new sister site dedicated to discussion of gold, silver, platinum, copper and palladium bar, coin, jewelry collecting/investing/storing/selling/buying. It would be greatly appreciated if you joined and help add a few new topics for new people to engage in.

Bullion.Forum

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Where are the alluvial gold bonanzas of the past?

- Thread starter user 4386

- Start date

-

- Tags

- alluvial gold

Help Support Prospecting Australia:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Skip said:Gold info Yella (pardon the pun)

That's a recent study and I'll take it on board,

So what I'm basically understanding is the older the land the more chance of gold.

No, not that simple. It has to be the right type of "old rock", and it depends at what stage of development of the bedrock in each area of the continent. The bedrock in South Australia is much older than that in Victoria, but placer gold is poor (wrong "type" of bedrock). WA goldfields even older but also poor in alluvial (placer) although plenty in bedrock veins. Pine Creek about same age as NT, bedrock veins OK but lack of mountains with rivers to form placers. Some of the gold-quartz veins in Queensland were still forming in younger bedrock when those in Victoria and much of Australia had already formed and were possibly already being eroded into placers.

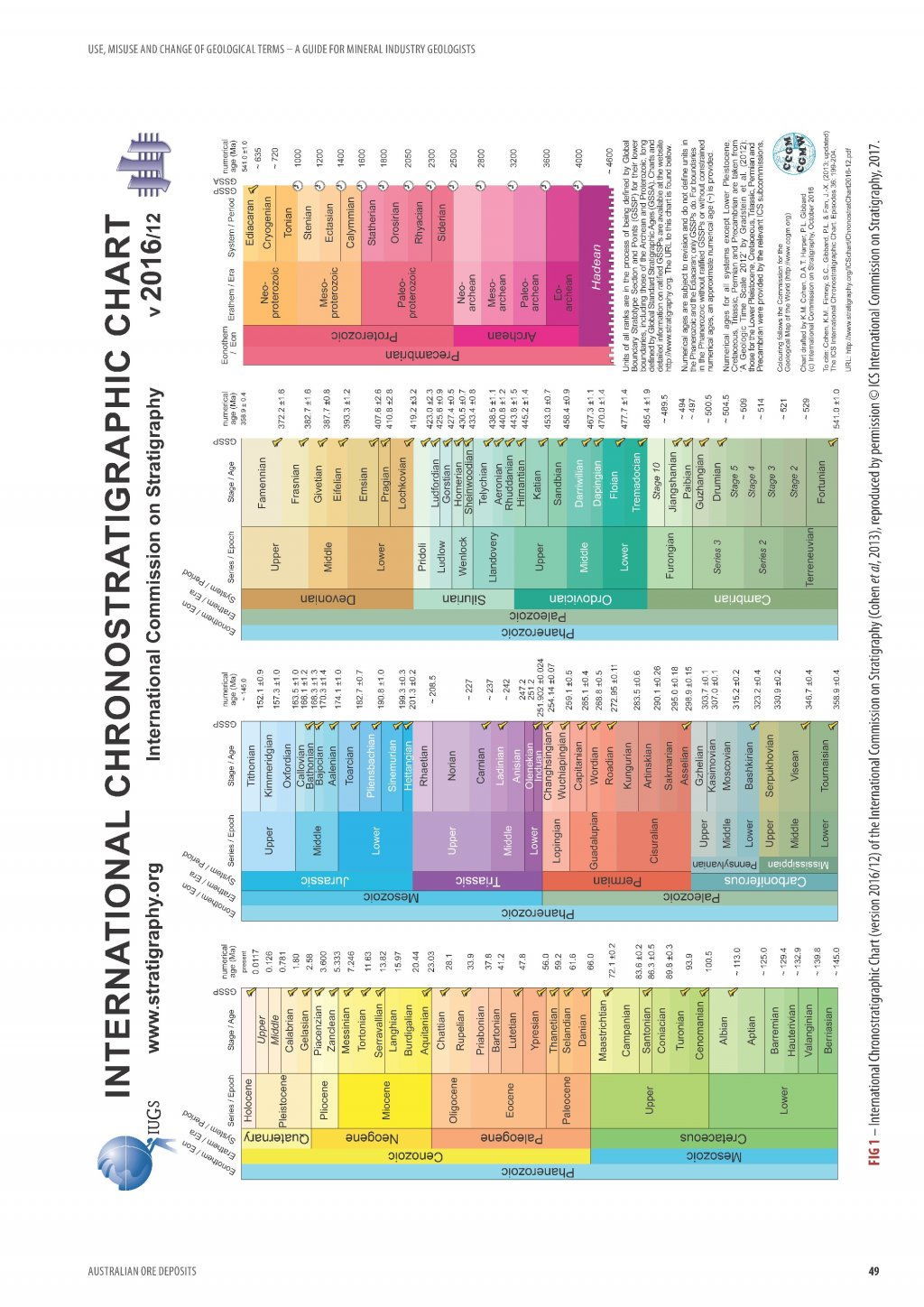

So the initial veins formed in rocks of age:

WA - Archaean (say 2700 million years)

SA and NT - Proterozoic (say 1500-700 million years)

Victoria, NSW and part of Queensland - Palaeozoic (say 500 million years) becoming Mesozoic (eg couple of hundred million) as you go north up coast

Northern and coastal Queensland (Mesozoic and younger - e.g. hundred million years)

Rock and veins kept forming even younger (tens of millions of years) but that part of Australia has since been rifted away as NZ and New Caledonia when the Tasman Sea opened. Gold veins there even younger (you can see gold still being formed in the hot spring system of North Island NZ). The New Zealand placers are therefore also younger.

And that is just the formation of the veins in bedrock - the formation of placers and how good they were then depended on deep weathering, uplift of mountains to give rivers etc. The NZ Alps only formed in the last two million years or less, before which NZ was a flat plain - our mountains of the Great Dividing Range started forming in Victoria as much as 200 million years ago and were uplifted again around 30 million years ago.

Up here in FNQ we have one gold field that is 90% alluvial, 10% hard rock, drive an hour south and it's reverse, 90% hard rock, 10% alluvial. Geology is amazing

Speaking of NZ, is there anywhere in Australia with evidence of glacially-transported gold, such as occurs in NZ and Alaska?

Mostly too far north for the last glacial periods. A few glaciers on higher areas in Tasmania and Kosciusko range. And even Antarctica lacked ice for some time prior to the latest - present- ice age (started about 2 My ago). Have to go back to the Permian (250 My) - rumoured to be some near Bacchus Marsh but I doubt it. Might be some that age in NSW but if so, insignificant. Could speculate that some around Beechworth- but also insignificant if so.

Few alluvial goldfields in Australia formed more than 60 My ago, give or take (Palaeocene-Eocene). A few formed in Cretaceous in NSW, approx. 150 My (eg edge of Sydney Basin), but they were fossil rivers, not glacial. Same age at Tibooburra.

Age chart attached.....sorry it is a PDF so cant do

Few alluvial goldfields in Australia formed more than 60 My ago, give or take (Palaeocene-Eocene). A few formed in Cretaceous in NSW, approx. 150 My (eg edge of Sydney Basin), but they were fossil rivers, not glacial. Same age at Tibooburra.

Age chart attached.....sorry it is a PDF so cant do

Where are the bonanzas of the past? i've often thought about this very question and this is what i came up with....

the bonanzas are still there but the easy ones have already been found. Some contributers to current situation...

1. mining licencing is so difficult the numberof people searching is simply not there.

2. so many people have combed over areas for the last 170 years that the breadcrums are simply not there to follow. - the trail is broken... what is worst is that someone might detect a few pieces somewhere but couldn't work out the source/pattern, but that info dies with them, the next person that walks over tha t hill has no idea that anything came out of the ground or that there might be more for that matter.

3. the oldtimers were so much more willing to rough it.... how many deep holes would an individual have dug past 6ft before they made wages? Bugger doing that now....

the bonanzas are still there but the easy ones have already been found. Some contributers to current situation...

1. mining licencing is so difficult the numberof people searching is simply not there.

2. so many people have combed over areas for the last 170 years that the breadcrums are simply not there to follow. - the trail is broken... what is worst is that someone might detect a few pieces somewhere but couldn't work out the source/pattern, but that info dies with them, the next person that walks over tha t hill has no idea that anything came out of the ground or that there might be more for that matter.

3. the oldtimers were so much more willing to rough it.... how many deep holes would an individual have dug past 6ft before they made wages? Bugger doing that now....

I think the real reason is that today people assume that the gold came out of present-day rivers, whereas this is incorrect and only a small part of it came from them. Most alluvial gold came from buried rivers many metres to tens and even hundreds of metres below surface, and few people dig shafts to those depths now (which overlaps with your last point, except that this was where MOST of the gold came from)..Eski said:Where are the bonanzas of the past? i've often thought about this very question and this is what i came up with....

the bonanzas are still there but the easy ones have already been found. Some contributers to current situation...

1. mining licencing is so difficult the numberof people searching is simply not there.

2. so many people have combed over areas for the last 170 years that the breadcrums are simply not there to follow. - the trail is broken... what is worst is that someone might detect a few pieces somewhere but couldn't work out the source/pattern, but that info dies with them, the next person that walks over tha t hill has no idea that anything came out of the ground or that there might be more for that matter.

3. the oldtimers were so much more willing to rough it.... how many deep holes would an individual have dug past 6ft before they made wages? Bugger doing that now....

The small amount from modern streams was further reduced by these being the "poor mans diggings" of the 1890s and 1930s depression, getting most of anything remaining).

- Joined

- Nov 24, 2013

- Messages

- 860

- Reaction score

- 1,581

Eski said:Where are the bonanzas of the past? i've often thought about this very question and this is what i came up with....

the bonanzas are still there but the easy ones have already been found. Some contributers to current situation...

1. mining licencing is so difficult the numberof people searching is simply not there.

2. so many people have combed over areas for the last 170 years that the breadcrums are simply not there to follow. - the trail is broken... what is worst is that someone might detect a few pieces somewhere but couldn't work out the source/pattern, but that info dies with them, the next person that walks over tha t hill has no idea that anything came out of the ground or that there might be more for that matter.

3. the oldtimers were so much more willing to rough it.... how many deep holes would an individual have dug past 6ft before they made wages? Bugger doing that now....

Couldnt agree more.

Detectorists who got viable gold in the last 40 years should have accurately mapped the location , not just because of the way a reef or other type of deposit can shear or uplift but because they were probably only detecting the top 12 - 24 inches.

Detectors now can reach 2 - 4 feet deep and could have maintained viability , even where there is gold that only had the surface picked off those could be mined using open cut mines.

Now we have to hope that modern Geo's walk over the area with an XRF and choose to explore further with drilling exploration or that its found with LiDAR or combinations of radiometric and geo sampling analytics to rediscover those locations.

You have to admire the tenacity of the old prospectors who would dig those ~ 10 - 30 metre deep shafts chasing the old leads , like you say most modern diggers wouldnt scrape past 6 inches yet the old timers averaged 200 dud shafts before they found viable lunch money.

How likely is it for retired prospectors to report "yeah i found 297 ounces at surface back in 1991 at 34 29' 48" S x 150 47' 42" E and i think there is more" ? Personally i would like to encourage such behaviour :lol:

i bet 23.5661 percent of prospectors will run those GPS numbers now . lol

I thought that since people liked my initial posts here, I would give you a bit more, as it may help your prospecting.

People panning in modern streams often don't understand that probably most Victorian alluvial gold did not come from gravels in flowing water, but in the same streams in gravels metres to hundreds of metres below what was the level of flowing streams when the miners arrived. That is one reason why gold was often only first discovered after a few people had frequented a goldfield area for some time (e.g. shepherds).

Here is a typical Victorian stream in hillier country. You can see that there is a rather limited volume of gravel in it, the stream typically flowing over hard bedrock. It could all be turned over by a couple of miners at a rate of tens of metres of stream per week, over a width of 10 m if you are lucky in many cases, from gravels that vary from 1 or max 2 metres deep, to more typically tens of centimetres deep confined between areas of outcropping bedrock. It could be very rich, but there was often little gravel volume, so total gold production was not huge unless you got a good patch, and the miners soon worked it out. Most people panning in streams are panning the recycled leftovers of worked gravel, biut if they dig out crevices in the floor of the stream they get a bit of gold missed by the old-timers..

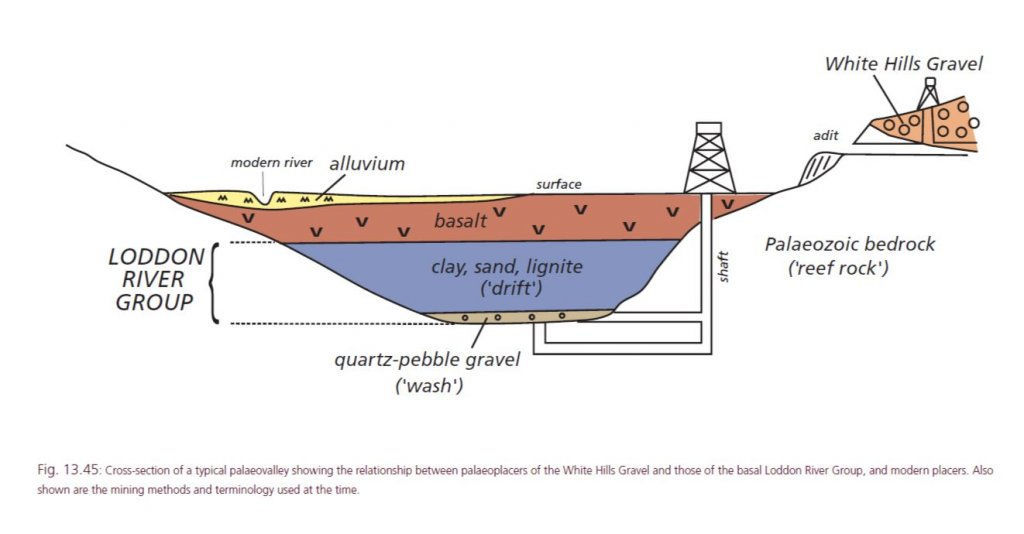

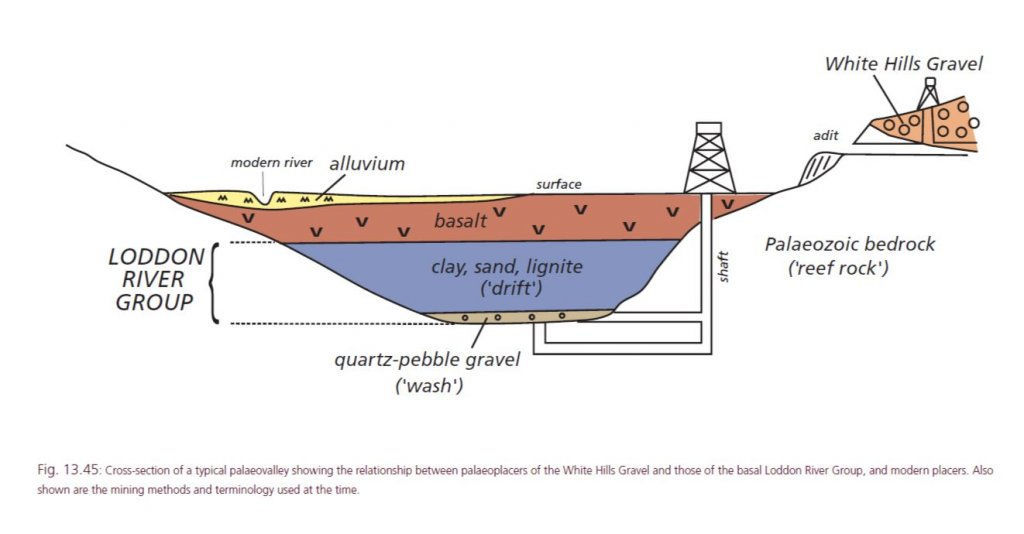

The reality is different in terms of where much alluvial gold came from (palaeoplacers). Alluvial production was from active stream systems (possibly a subordinate part of the total production), and on adjacent flats where buried river gravels were mined to depths of 30 m. It is difficult to determine how much of the shallow placer gold production of the Western Uplands was mined from Pliocene and younger sediments, relative to that produced from underlying, older but shallow, palaeoplacers. Much was probably recycled from gravel deposited at an earlier time, e.g. in the headwaters of Loddon River Group drainages. Older gravels of this type appear to have been mined from beneath younger colluvial deposits in the shallower alluvial gold workings of many goldfields (e.g. Ballarat).

Look at this gully. The water level was probably nearly 2 m higher than the base of the valley now, a bit swampy and ill-defined - allowing for 150 years of crap washing in, the gravels they were mining were probably below the present base of this gully, perhaps a metre or so (so 2-3 m below the water. Although in the same valley, and followed by a modern gully, the original gully and gold-rich gravels probably formed millions of years earlier.

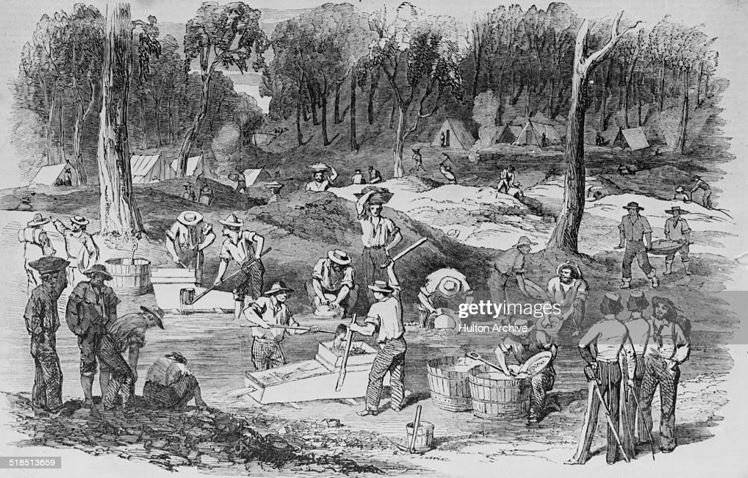

Now look at this drawing done in goldfield times, and see the low mine dumps behind the opposite side of the gully.

These dumps were from shallow shafts, perhaps a few metres to ten metres deep, from which the miners were extracting gold-bearing gravel millions to probably often 15-30 million years old. Again, in the same valley, but offset from the modern flowing stream. Younger streams have successively moved back and forward sideways in the valley, covering these early gravels with clay and sand, and themselves have some gravel in them, but only a small volume. The ancient gravels were up to 50 metres wide in places (bigger rivers) and a good continuous layer of gravel in them 0.5 to 1 m thick was taken up the shafts. What they are doing in the picture is washing the gravel that they brought up the shafts in the modern flowing stream, often not working the modern stream itself, and all the waste crap they were bringing up was ending up in the modern stream. So when you pan the flowing stream now you are often panning a stream that never had much gold in it to start with, but which contains lots of gravel brought up the shafts (from which the gold had already been extracted). The miners would say they were working a "shallow lead" from their shafts.

You can see from this map of the Ballarat goldfield how the gold leads such as the Inkerman and Mopoke do not follow even the modern valleys (the Mopoke Lead cuts across modern Yarrowee Creek at right-angles in the bottom-right of the map.

After they finished (and 150 years) their shallow shafts now look like this.

You will commonly see these low mounds off to one side of the modern flowing stream, metres to tens of metres off to the side of it. The detectorologists often do better detecting these mounds (because the old miners mistakenly dumped some good gravel beside the shaft that they had brought up), than do the panners who now try working the stream.

Variations on the theme is that earthquakes have sometimes uplifted the old gravels, so that they are now on hillsides or hilltops above the modern streams (see White Hills Gravel in section). Another is that the old miners had limited resources and machinery, so usually only followed buried river gravels until they got more than 30 m below surface. Then goldfields went quiet and they moved on, later companies and syndicates moved in with good pumps and started to continue mining the gravels to greater depths (more than 150 m at Ballarat West). These were called "deep leads" (see bottom of palaeovalley in section).

Hope that helps.

People panning in modern streams often don't understand that probably most Victorian alluvial gold did not come from gravels in flowing water, but in the same streams in gravels metres to hundreds of metres below what was the level of flowing streams when the miners arrived. That is one reason why gold was often only first discovered after a few people had frequented a goldfield area for some time (e.g. shepherds).

Here is a typical Victorian stream in hillier country. You can see that there is a rather limited volume of gravel in it, the stream typically flowing over hard bedrock. It could all be turned over by a couple of miners at a rate of tens of metres of stream per week, over a width of 10 m if you are lucky in many cases, from gravels that vary from 1 or max 2 metres deep, to more typically tens of centimetres deep confined between areas of outcropping bedrock. It could be very rich, but there was often little gravel volume, so total gold production was not huge unless you got a good patch, and the miners soon worked it out. Most people panning in streams are panning the recycled leftovers of worked gravel, biut if they dig out crevices in the floor of the stream they get a bit of gold missed by the old-timers..

The reality is different in terms of where much alluvial gold came from (palaeoplacers). Alluvial production was from active stream systems (possibly a subordinate part of the total production), and on adjacent flats where buried river gravels were mined to depths of 30 m. It is difficult to determine how much of the shallow placer gold production of the Western Uplands was mined from Pliocene and younger sediments, relative to that produced from underlying, older but shallow, palaeoplacers. Much was probably recycled from gravel deposited at an earlier time, e.g. in the headwaters of Loddon River Group drainages. Older gravels of this type appear to have been mined from beneath younger colluvial deposits in the shallower alluvial gold workings of many goldfields (e.g. Ballarat).

Look at this gully. The water level was probably nearly 2 m higher than the base of the valley now, a bit swampy and ill-defined - allowing for 150 years of crap washing in, the gravels they were mining were probably below the present base of this gully, perhaps a metre or so (so 2-3 m below the water. Although in the same valley, and followed by a modern gully, the original gully and gold-rich gravels probably formed millions of years earlier.

Now look at this drawing done in goldfield times, and see the low mine dumps behind the opposite side of the gully.

These dumps were from shallow shafts, perhaps a few metres to ten metres deep, from which the miners were extracting gold-bearing gravel millions to probably often 15-30 million years old. Again, in the same valley, but offset from the modern flowing stream. Younger streams have successively moved back and forward sideways in the valley, covering these early gravels with clay and sand, and themselves have some gravel in them, but only a small volume. The ancient gravels were up to 50 metres wide in places (bigger rivers) and a good continuous layer of gravel in them 0.5 to 1 m thick was taken up the shafts. What they are doing in the picture is washing the gravel that they brought up the shafts in the modern flowing stream, often not working the modern stream itself, and all the waste crap they were bringing up was ending up in the modern stream. So when you pan the flowing stream now you are often panning a stream that never had much gold in it to start with, but which contains lots of gravel brought up the shafts (from which the gold had already been extracted). The miners would say they were working a "shallow lead" from their shafts.

You can see from this map of the Ballarat goldfield how the gold leads such as the Inkerman and Mopoke do not follow even the modern valleys (the Mopoke Lead cuts across modern Yarrowee Creek at right-angles in the bottom-right of the map.

After they finished (and 150 years) their shallow shafts now look like this.

You will commonly see these low mounds off to one side of the modern flowing stream, metres to tens of metres off to the side of it. The detectorologists often do better detecting these mounds (because the old miners mistakenly dumped some good gravel beside the shaft that they had brought up), than do the panners who now try working the stream.

Variations on the theme is that earthquakes have sometimes uplifted the old gravels, so that they are now on hillsides or hilltops above the modern streams (see White Hills Gravel in section). Another is that the old miners had limited resources and machinery, so usually only followed buried river gravels until they got more than 30 m below surface. Then goldfields went quiet and they moved on, later companies and syndicates moved in with good pumps and started to continue mining the gravels to greater depths (more than 150 m at Ballarat West). These were called "deep leads" (see bottom of palaeovalley in section).

Hope that helps.

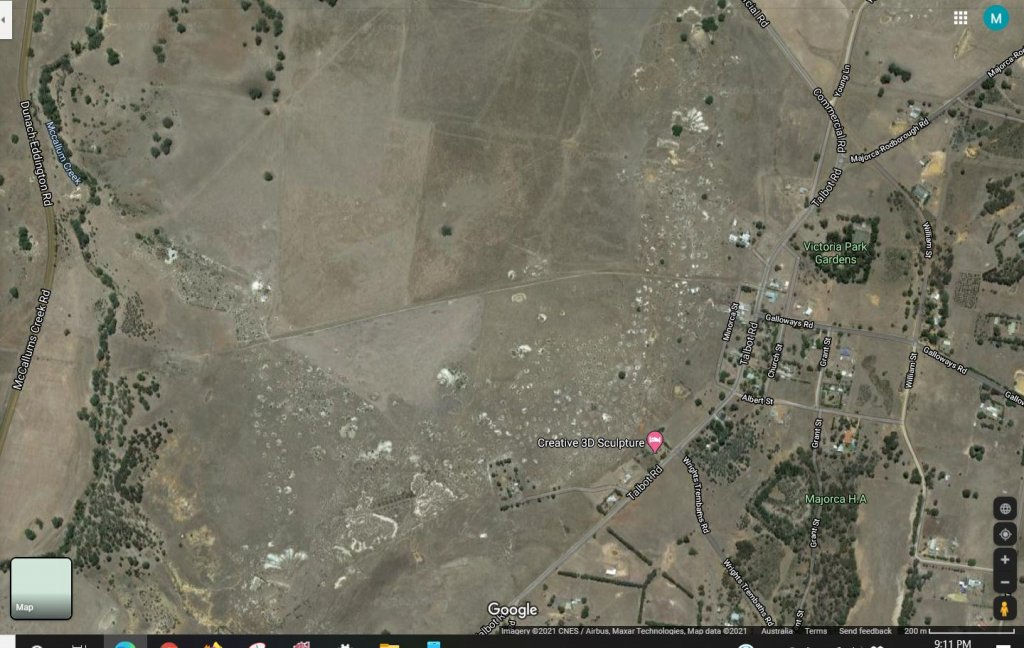

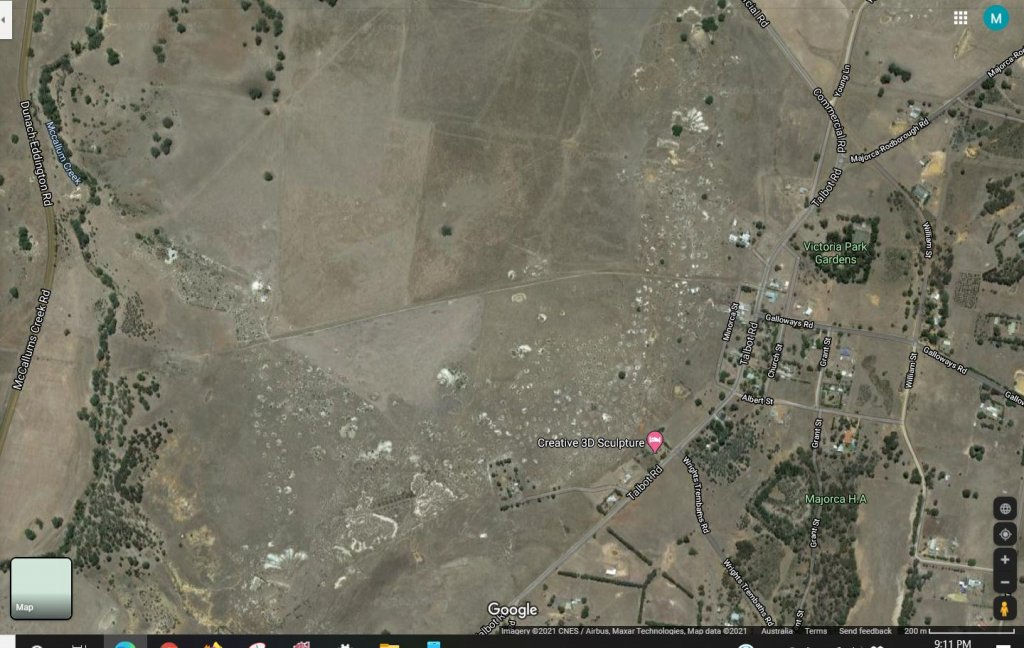

Here is an aerial photo of an area where the old mine dumps on leads have not been rehabilitated by farmers, and are not concealed by trees. You can see the linear trend of the old palaeoplacer shafts (white) on a lead, and how they don't follow modern streams (which are partly outlined by dark trees along their banks).

And here is a photo of one of the above shafts on the aerial photo - often not very obvious now

And here is a photo of one of the above shafts on the aerial photo - often not very obvious now

Absolutely brilliant work and I only have one question, where were you forty years ago when I needed this knowledge, just kidding mate, that is amazing. Thank You

Mackka

Mackka

Thanks.Mackka said:Absolutely brilliant work and I only have one question, where were you forty years ago when I needed this knowledge, just kidding mate, that is amazing. Thank You

Mackka

40 years ago - probably in the Canadian Arctic

No sorry - Africa

Goldierocks wote :" Here is a typical Victorian stream in hillier country. You can see that there is a rather limited volume of gravel in it, the stream typically flowing over hard bedrock. It could all be turned over by a couple of miners at a rate of tens of metres of stream per week, over a width of 10 m if you are lucky in many cases, from gravels that vary from 1 or max 2 metres deep, to more typically tens of centimetres deep confined between areas of outcropping bedrock. It could be very rich, but there was often little gravel volume, so total gold production was not huge unless you got a good patch, and the miners soon worked it out. Most people panning in streams are panning the recycled leftovers of worked gravel, biut if they dig out crevices in the floor of the stream they get a bit of gold missed by the old-timers.."

Were the Streams that deposited the Ellivated Terrace deposits typically found on the sides of hills and mountains sometimes Hundreds of metres above the present day streams in the upper Mitta, Ovens, Buckland, Kiewa, Dargo Tambo Etc formed at the same time as the Palioplacer deep leads in central western Vic? I know that deepleads were traced under the older volcanics at Brandy Creek near mount Hotham and other places where streams have cut down through these older volcanics exposing buried stream systems.

I was also wondering why coarse nuggety gold is much more prevalent in the central western Goldfields than it is in the goldfields of eastern Victoria that typically have these ellivated terraces.

Were the Streams that deposited the Ellivated Terrace deposits typically found on the sides of hills and mountains sometimes Hundreds of metres above the present day streams in the upper Mitta, Ovens, Buckland, Kiewa, Dargo Tambo Etc formed at the same time as the Palioplacer deep leads in central western Vic? I know that deepleads were traced under the older volcanics at Brandy Creek near mount Hotham and other places where streams have cut down through these older volcanics exposing buried stream systems.

I was also wondering why coarse nuggety gold is much more prevalent in the central western Goldfields than it is in the goldfields of eastern Victoria that typically have these ellivated terraces.

Good questions.

Re age - yes, probably in some cases a similar age, less so for terraces, because we find that some in the eat (eg east of Dargo) were uplifted only shortly after that time, and we find quite old basalt flows in valleys that subsequently cut into them.

And there are probably two reasons for the nugget distribution. One is that the type of gold deposits in the east from which the alluvial gold there was derived typically lacked coarse gold relative to central Victoria, much gold being fine and locked inside sulphide minerals (I have a paper that I could give you on this if you PM). Another is that some nuggets probably "grow" in the weathering zone, and that the early weathering veneer has been fairly efficiently eroded away in the east long ago (but I think this might be a less important reason than the first). Likewise I can forward a paper on this.

One theory is that Victoria was all fairly deeply-weathered and low relief in the Palaeogene (which used to be called Early Tertiary). The deep weathering had reduced the rock near surface to clay, sand, quartz, ironstone and gold. Uplift then occurred, and the more numerous and active streams that resulted washed the sand and clay away, but tended to concentrate vein quartz pebbles, ironstone and gold close to its source because these were high SG minerals, or larger VEIN QUARTZ pebbles and cobbles that were more resistant to breaking down (i.e. there were few actual ROCK pebbles and cobbles left because of the earlier weathering). When we look at those palaeoplacers we find that a large proportion of the fragments in them are vein quartz rather than rock fragments - so the gold was also greatly enriched in them because only these resistant items had been concentrated and much of the original rock volume removed. Later, younger streams have partly redistributed this early material (eg in modern streams and their slightly older terraces), but if you look at these later gravels and conglomerates, the proportion of rock fragments relative to vein quartz fragments is much greater, and they tend to be less rich in gold. So the gravels formed immediately after uplift (eg many of the central Victorian leads, perhaps those under the basalt east from Dargo) tend to be the rich ones or at least to have mostly vein quartz pebbles- others such as the Mitta Mitta terraces tend to be lower grade and were only economic because of their greater volume, and because modern topography permitted large-scale hydraulic sluicing and dredging. Also discussed in one paper.

Re age - yes, probably in some cases a similar age, less so for terraces, because we find that some in the eat (eg east of Dargo) were uplifted only shortly after that time, and we find quite old basalt flows in valleys that subsequently cut into them.

And there are probably two reasons for the nugget distribution. One is that the type of gold deposits in the east from which the alluvial gold there was derived typically lacked coarse gold relative to central Victoria, much gold being fine and locked inside sulphide minerals (I have a paper that I could give you on this if you PM). Another is that some nuggets probably "grow" in the weathering zone, and that the early weathering veneer has been fairly efficiently eroded away in the east long ago (but I think this might be a less important reason than the first). Likewise I can forward a paper on this.

One theory is that Victoria was all fairly deeply-weathered and low relief in the Palaeogene (which used to be called Early Tertiary). The deep weathering had reduced the rock near surface to clay, sand, quartz, ironstone and gold. Uplift then occurred, and the more numerous and active streams that resulted washed the sand and clay away, but tended to concentrate vein quartz pebbles, ironstone and gold close to its source because these were high SG minerals, or larger VEIN QUARTZ pebbles and cobbles that were more resistant to breaking down (i.e. there were few actual ROCK pebbles and cobbles left because of the earlier weathering). When we look at those palaeoplacers we find that a large proportion of the fragments in them are vein quartz rather than rock fragments - so the gold was also greatly enriched in them because only these resistant items had been concentrated and much of the original rock volume removed. Later, younger streams have partly redistributed this early material (eg in modern streams and their slightly older terraces), but if you look at these later gravels and conglomerates, the proportion of rock fragments relative to vein quartz fragments is much greater, and they tend to be less rich in gold. So the gravels formed immediately after uplift (eg many of the central Victorian leads, perhaps those under the basalt east from Dargo) tend to be the rich ones or at least to have mostly vein quartz pebbles- others such as the Mitta Mitta terraces tend to be lower grade and were only economic because of their greater volume, and because modern topography permitted large-scale hydraulic sluicing and dredging. Also discussed in one paper.

Thanks Goldie. Ive read you very detailed and concise reply to my questions through a few times and I have a bad feeling that Im gunna be doing a lot of reading to expand my limited knowledge on the subject of Fine alluvial gold derived from the weathering of Auriferrous Lode Systems versus the Coarse Gold found in the Central and southwestern goldfields. PM incoming regards the papers mentioned above. :Y:

Tiber

Rob

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2022

- Messages

- 2

- Reaction score

- 1

OK goldie, I've this thread 6 times and understood 12.36 % of it!! If I understand you correctly, firstly, if you don't know geology you're wasting a lot of time, secondly, there's not much river gold that originates from the stream itself, and thirdly, most alluvial gold comes from paleoplacers through the action of geological uplift (of ancients layers) and the work of erosion, whether rain or river. Fourthly, if you want serious gold, you've got to dig deep and in the right spot. Few of us are in a position to dig a mine shaft, so alluvial gold by detection seems to be the best bet. Question is; how to find the likely place of a paleoplacer "lift" and its "downhill" region where there might be surface gold? Is this possible for the amateur? Can you do it on Geovic? Do you have to be able to read a detailed geological map? Any guidance on this would be greatly appreciated.Good questions.

Re age - yes, probably in some cases a similar age, less so for terraces, because we find that some in the eat (eg east of Dargo) were uplifted only shortly after that time, and we find quite old basalt flows in valleys that subsequently cut into them.

And there are probably two reasons for the nugget distribution. One is that the type of gold deposits in the east from which the alluvial gold there was derived typically lacked coarse gold relative to central Victoria, much gold being fine and locked inside sulphide minerals (I have a paper that I could give you on this if you PM). Another is that some nuggets probably "grow" in the weathering zone, and that the early weathering veneer has been fairly efficiently eroded away in the east long ago (but I think this might be a less important reason than the first). Likewise I can forward a paper on this.

One theory is that Victoria was all fairly deeply-weathered and low relief in the Palaeogene (which used to be called Early Tertiary). The deep weathering had reduced the rock near surface to clay, sand, quartz, ironstone and gold. Uplift then occurred, and the more numerous and active streams that resulted washed the sand and clay away, but tended to concentrate vein quartz pebbles, ironstone and gold close to its source because these were high SG minerals, or larger VEIN QUARTZ pebbles and cobbles that were more resistant to breaking down (i.e. there were few actual ROCK pebbles and cobbles left because of the earlier weathering). When we look at those palaeoplacers we find that a large proportion of the fragments in them are vein quartz rather than rock fragments - so the gold was also greatly enriched in them because only these resistant items had been concentrated and much of the original rock volume removed. Later, younger streams have partly redistributed this early material (eg in modern streams and their slightly older terraces), but if you look at these later gravels and conglomerates, the proportion of rock fragments relative to vein quartz fragments is much greater, and they tend to be less rich in gold. So the gravels formed immediately after uplift (eg many of the central Victorian leads, perhaps those under the basalt east from Dargo) tend to be the rich ones or at least to have mostly vein quartz pebbles- others such as the Mitta Mitta terraces tend to be lower grade and were only economic because of their greater volume, and because modern topography permitted large-scale hydraulic sluicing and dredging. Also discussed in one paper.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 19

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 879

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 1K