Absolutely beautiful job of telling this story Jemba...very much in the vein of some of my grandfathers reminiscence of stories passed down to him of those members of my family recalled of having been around at the time...Your layout and flowing nature of your commentry and graphic placement for where it will have best impact are obvious mate..I'm really enjoying this...looking at those undaunted souls all camped out and 6feet deep...Temporary windlass to raise the buckets and washout before tea.!hehe....great stuff mate.

-

Please join our new sister site dedicated to discussion of gold, silver, platinum, copper and palladium bar, coin, jewelry collecting/investing/storing/selling/buying. It would be greatly appreciated if you joined and help add a few new topics for new people to engage in.

Bullion.Forum

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

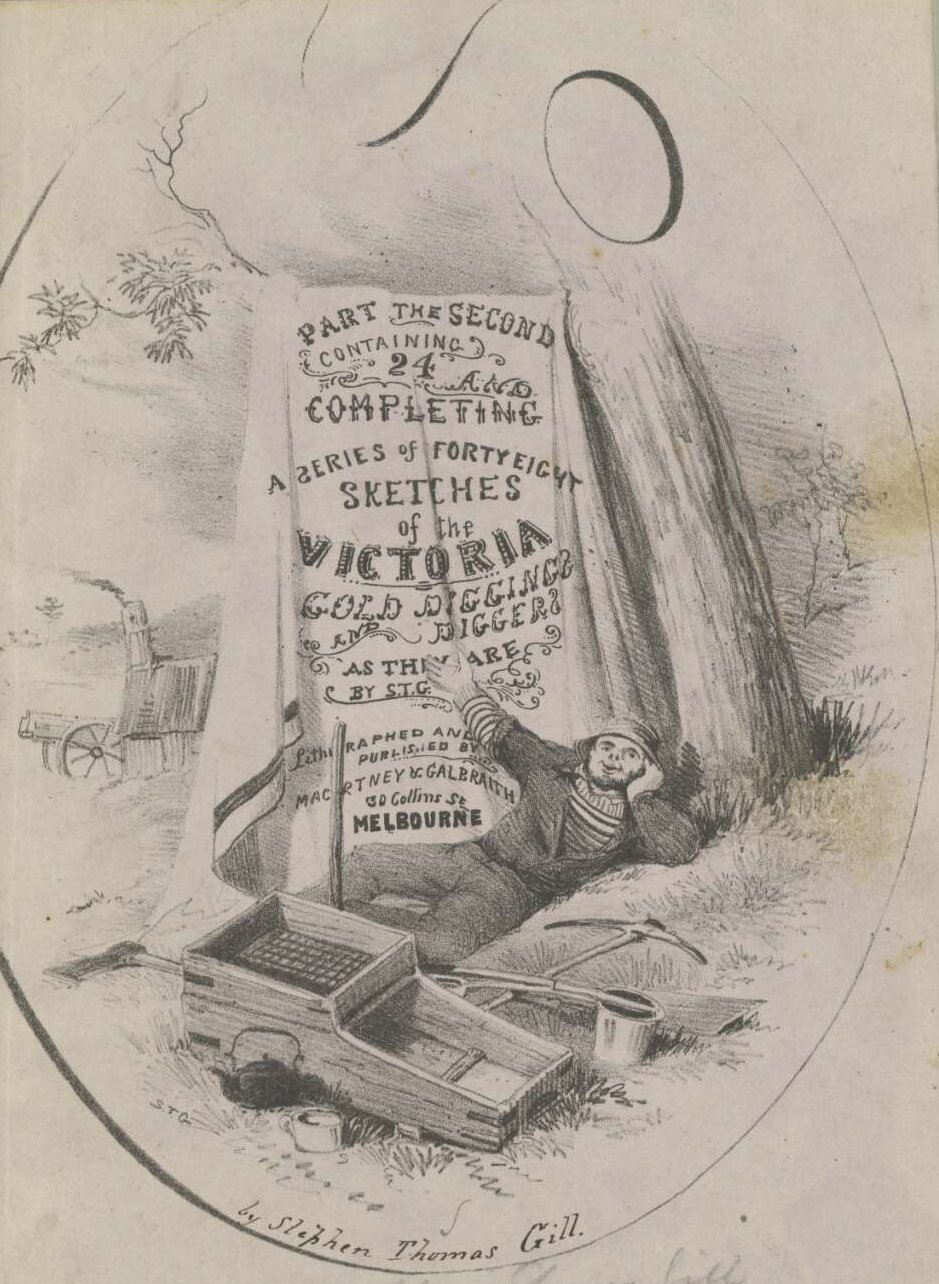

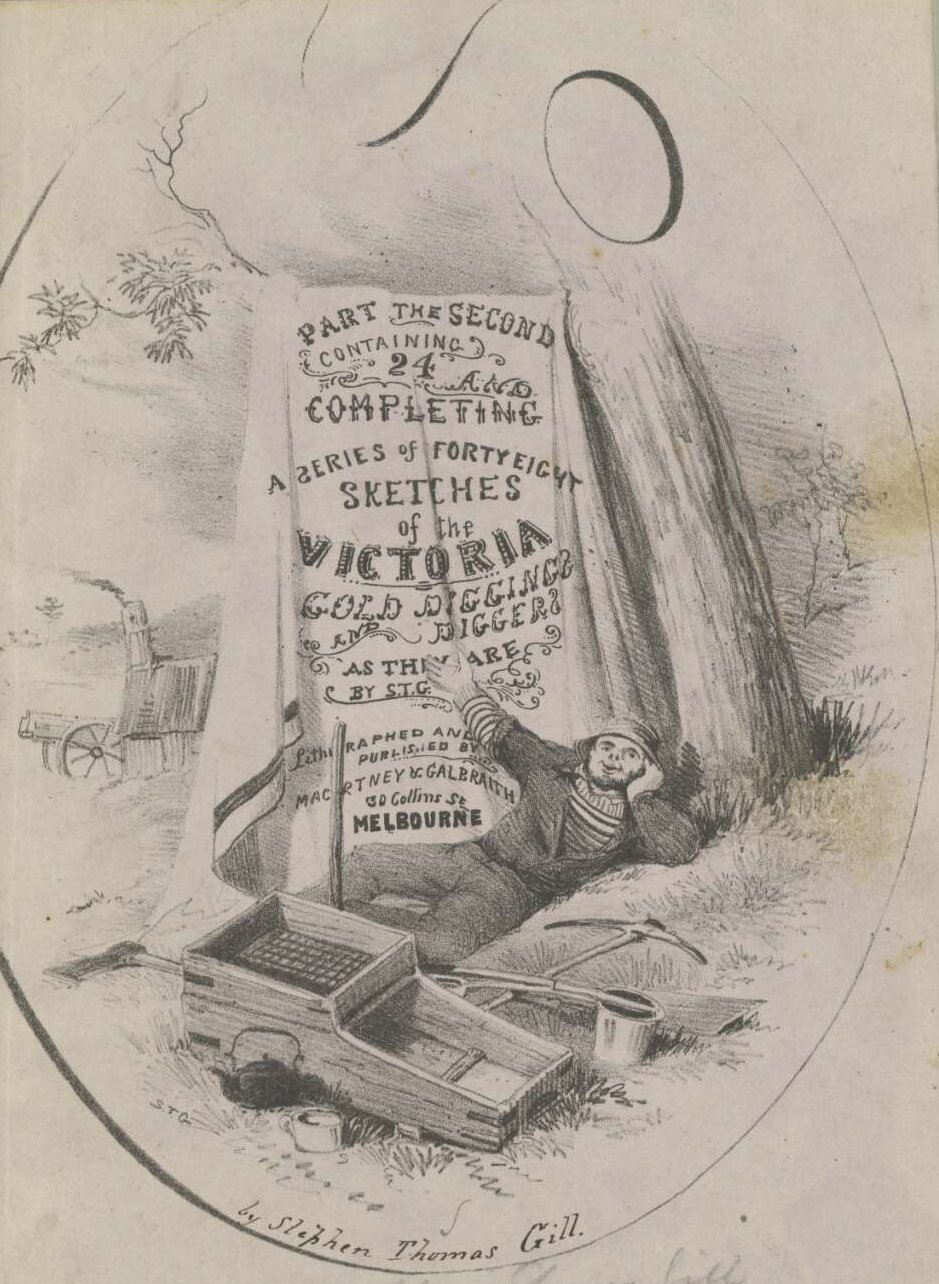

REMINISCENCES OF THE OLD GOLD DIGGERS.

- Thread starter Jemba

- Start date

Help Support Prospecting Australia:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Absolutely beautiful job of telling this story Jemba...very much in the vein of some of my own work here in short stories!... :trophy:...not that the same can be said of me getting a cup for one of mine..... :lol: I mean it though mate ...makes great reading...and full of so much helpful ideas and My Pop would come up with his reminiscence of stories passed down to him of those members of my family recalling of having been around at the time...Your layout and flowing nature of your commentry and graphic placement for where it will have best impact are obvious mate..I'm really enjoying this...looking at those undaunted souls all camped out and 6feet deep in the shaft already...Temporary windlass to raise the buckets and washout before tea.!hehe....great stuff mate.

Thanks Reefer it is good to know what people think. For the new chum who is reading this, my advice is this, if you select an area or field you wish to work. Obtain as much information on that area as you can. Instead of going from field to field get to know one area like the back of your hand. How the area was worked the type of material the gold was found in, was it a rich field with good returns and so on. After all as they say to know where were going, we must first know where were been.

Cheers

Jemba

As an example of what research can do for you. A typical day prospecting for me.

lunch time clean up.

End of day take home concentrate

home cleanup

Cheers

Jemba

As an example of what research can do for you. A typical day prospecting for me.

lunch time clean up.

End of day take home concentrate

home cleanup

Couldn't agreed more Jemba. Research,Research and Research and more Research. That is a very pretty site mate.

Cheers and Keep up the Excellent work.

Mackka erfect:

erfect:

Cheers and Keep up the Excellent work.

Mackka

Hi Mackka yes indeed. As a rule I don't like posting photos of my finds or my adventures, but when pans look like the ones below well what more can I say. Only this and I am more or less addressing the new chum, popular areas are a good place to learn but a bad place to get serious. You must remember that what you have read and learnt from books and such, so has others and have done so, over the last 100 odd years or so. You must also remember to respect the land holders right's. Do this and you will have a ball.

cheers

Jemba

cheers

Jemba

I don't think WOW, covers it, but, WOW!

Mackka

Mackka

IN THE NICK OF TIME.

One morning, seventy-two years ago, young Charlie Cook was working' at the claim with his father, at Chow Flat. Now where was Chow Flat? Well, it was in the vicinity of Wattle Flat, which is three or four miles from Sofala. The little creek that drained the flat made its way down into Bell's creek, which enters the Turon river below Springs creek, which yielded "Roger's Nugget." I trust that, after all that explanation, Chow Flat will stand out conspicuously as a blind boil on the end of the reader's nose. There are so many creeks and flats associated with mining fields, that one has to be explicit in locating them. Now, let's get back to Charlie. He was in charge of the puddling-tub and cradle, while his father was "kyooting" after some washdirt, so as to save stripping six or eight feet of overburden. The wash was puggy and had to be puddled well before it was put through the cradle.

Things were looking blue with the Cook family where there were ten mouths to feed. The storekeepers at Wattle Flat and Sofala had stopped Dad Cook's credit, which brought things to a crisis that day, seventy-two years agone, when the kyooting was going on. It was just a forlorn hope. Chinamen had worked around the spot, and Chinese rarely leave ground till they've taken the last available speck of gold. Cook carried the washdirt to the boy in buckets, piling the yellow stuff in a heap beside the tub, which the lad was stirring vigorously. Charlie doubted whether they would make a penny weight the whole day.

He was feeling the tucker-pinch at home, and he was gloomy and dull in spirit. Draining off the yellow sludge from the tub, he shovelled the gravel, into the cradle-hopper, and started rocking with his left hand, and ladling water in with his long-handled pot. Rattle, rattle, went the stones, and the fine stuff disappeared gradually through the holes of the hopper. Charlie shovelled in more washdirt. and kept on with his rocking. Thud, thud went his father's pick twenty yards away. The boy seized the hopper, lifted it out, and was about to toss out the stones, when, "Christopher Columbus!" he yelled, as he picked out a beautiful glittering nugget weighing ten ounces! They had Irish stew for supper that night.

Camperdown Chronicle Thursday 16 July 1936

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

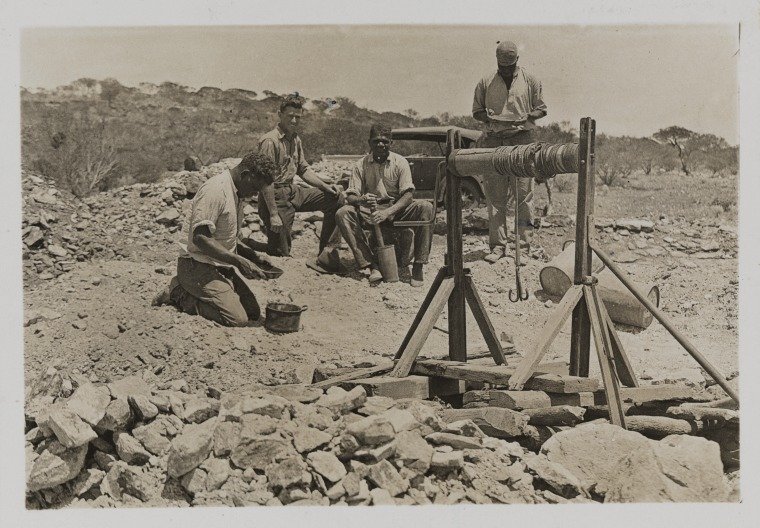

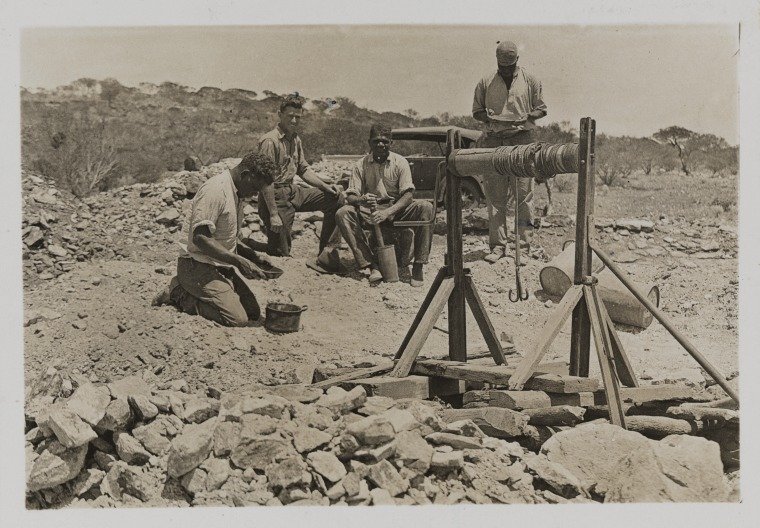

Mining in the Mount Margaret Goldfield.

https://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b4054340_1

Shallow mine shaft, Oaks Goldfield, Queensland

https://nqheritage.jcu.edu.au/150/

One morning, seventy-two years ago, young Charlie Cook was working' at the claim with his father, at Chow Flat. Now where was Chow Flat? Well, it was in the vicinity of Wattle Flat, which is three or four miles from Sofala. The little creek that drained the flat made its way down into Bell's creek, which enters the Turon river below Springs creek, which yielded "Roger's Nugget." I trust that, after all that explanation, Chow Flat will stand out conspicuously as a blind boil on the end of the reader's nose. There are so many creeks and flats associated with mining fields, that one has to be explicit in locating them. Now, let's get back to Charlie. He was in charge of the puddling-tub and cradle, while his father was "kyooting" after some washdirt, so as to save stripping six or eight feet of overburden. The wash was puggy and had to be puddled well before it was put through the cradle.

Things were looking blue with the Cook family where there were ten mouths to feed. The storekeepers at Wattle Flat and Sofala had stopped Dad Cook's credit, which brought things to a crisis that day, seventy-two years agone, when the kyooting was going on. It was just a forlorn hope. Chinamen had worked around the spot, and Chinese rarely leave ground till they've taken the last available speck of gold. Cook carried the washdirt to the boy in buckets, piling the yellow stuff in a heap beside the tub, which the lad was stirring vigorously. Charlie doubted whether they would make a penny weight the whole day.

He was feeling the tucker-pinch at home, and he was gloomy and dull in spirit. Draining off the yellow sludge from the tub, he shovelled the gravel, into the cradle-hopper, and started rocking with his left hand, and ladling water in with his long-handled pot. Rattle, rattle, went the stones, and the fine stuff disappeared gradually through the holes of the hopper. Charlie shovelled in more washdirt. and kept on with his rocking. Thud, thud went his father's pick twenty yards away. The boy seized the hopper, lifted it out, and was about to toss out the stones, when, "Christopher Columbus!" he yelled, as he picked out a beautiful glittering nugget weighing ten ounces! They had Irish stew for supper that night.

Camperdown Chronicle Thursday 16 July 1936

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

Mining in the Mount Margaret Goldfield.

https://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b4054340_1

Shallow mine shaft, Oaks Goldfield, Queensland

https://nqheritage.jcu.edu.au/150/

DIGGING FOR GOLD

WHEN the regiment first moved into an old gold mining area, the gunners were highly enthusiastic about digging sanitary and ammunition pits. It made your blood tingle to think that maybe the next shovel full of clay would uncover a second Welcome Nugget. But the gold fever burned itself out within two days when not even a color was found. And it stayed out for two months until a whisper went round that Joe Shropper, generally known as The Boy from . Bendigo, had something up his sleeve.

Now Joe had often boasted about the gold he had unearthed in his home town, and memories of his tall stories came crowding back into our minds. If gold was to be found, Joe was the boy to do the trick. Every gunner in camp tried to get beside Shropper and the Battery Sar-Major almost went out of his way to be kind to him,, especially when he heard that Joe had a parcel of something locked in his kit bag. When excitement reached fever pitch, Joe let it be known that he would make a statement in the gunners mess one evening. Everyone turned up, including the orderly officer in case a riot might occur. Someone called for silence, and Joe stood up on a table. For a few suspenseful seconds he was silent. His fingers went into his shirt pocket. We held our breaths. Joe held up a lump of rock to which was attached a lump of gold as big as your little finger-nail. Gold! we all said. Reckon Ive unearthed the mother lode which was lost 50 years ago, declared Joe. Where is it? we shouted. Ah! said Joe and went to move off. . But we forced him to stay on the table. OK, he declared. I wont be greedy. Ill float a small company with 30 shareholders at a quid a head. Then well split the profits. Anyone wanting a share come to my tent in the morning.

A crowd of us turned up to find Joe waiting with the articles of association of the Joe Shropper Mother Load No Liarbillytee. Joe was to be general manager, secretary, treasurer and board of directors. He was to receive 30 cash for his rights, and all gold won was to be shared equally between the 30 shareholders and himself. Why cant some of us be on the board of directors? queried Charlie the old gunner. If you aint satisfied with the terms you can nick off, - said Joe rudely. Im only letting you ave shares as a favor. OK, Joe, no offence, Charlie cooed. We all signed a paper to the effect that we agreed with Joes terms, and paid over our quids. Sunday, being rest day, was selected as the moment we should attack the mother lode and tear a fortune from it. Good old Joe! By dawn light we followed the general manager to a hole in the river bank and watched in admiration as he marked out strips around the hole where we were to dig. At midday we were down six feet and picking at solid rock. Joe was shouting, Throw me up samples, boys, and studying bits of brown stone with a magnifying glass like a government geologist.

By four oclock even Joe had to admit that we hadnt found, an Eldorado. Its funny, he declared mournfully, Id have staked my life Id found the lode after digging out that gold I showed you. Still, it cant be helped. , You know what goldmining is. Either your lucks in or its out. This time its out. But what about our 30? growled Charlie the old gunner. Well, now. declared Joe. Fair go. You risked it knowingly and you lost it. He waved his hands in the air. Charlie looked hard at the waving hands and said a very rude word. Say, Shropper, he shouted, wheres that gold ring you used to wear? Joe went pale and muttered: I lost it a few days ago. You melted It down and stuck it in the rock, roared Charlie. Joe tried to bolt, but we collared him, administered summary justice, and from his belt took that which was our own. We let him keep our contracts.

By SMITHS STAFF REPORTER

Smith's Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1919 - 1950)

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

WHEN the regiment first moved into an old gold mining area, the gunners were highly enthusiastic about digging sanitary and ammunition pits. It made your blood tingle to think that maybe the next shovel full of clay would uncover a second Welcome Nugget. But the gold fever burned itself out within two days when not even a color was found. And it stayed out for two months until a whisper went round that Joe Shropper, generally known as The Boy from . Bendigo, had something up his sleeve.

Now Joe had often boasted about the gold he had unearthed in his home town, and memories of his tall stories came crowding back into our minds. If gold was to be found, Joe was the boy to do the trick. Every gunner in camp tried to get beside Shropper and the Battery Sar-Major almost went out of his way to be kind to him,, especially when he heard that Joe had a parcel of something locked in his kit bag. When excitement reached fever pitch, Joe let it be known that he would make a statement in the gunners mess one evening. Everyone turned up, including the orderly officer in case a riot might occur. Someone called for silence, and Joe stood up on a table. For a few suspenseful seconds he was silent. His fingers went into his shirt pocket. We held our breaths. Joe held up a lump of rock to which was attached a lump of gold as big as your little finger-nail. Gold! we all said. Reckon Ive unearthed the mother lode which was lost 50 years ago, declared Joe. Where is it? we shouted. Ah! said Joe and went to move off. . But we forced him to stay on the table. OK, he declared. I wont be greedy. Ill float a small company with 30 shareholders at a quid a head. Then well split the profits. Anyone wanting a share come to my tent in the morning.

A crowd of us turned up to find Joe waiting with the articles of association of the Joe Shropper Mother Load No Liarbillytee. Joe was to be general manager, secretary, treasurer and board of directors. He was to receive 30 cash for his rights, and all gold won was to be shared equally between the 30 shareholders and himself. Why cant some of us be on the board of directors? queried Charlie the old gunner. If you aint satisfied with the terms you can nick off, - said Joe rudely. Im only letting you ave shares as a favor. OK, Joe, no offence, Charlie cooed. We all signed a paper to the effect that we agreed with Joes terms, and paid over our quids. Sunday, being rest day, was selected as the moment we should attack the mother lode and tear a fortune from it. Good old Joe! By dawn light we followed the general manager to a hole in the river bank and watched in admiration as he marked out strips around the hole where we were to dig. At midday we were down six feet and picking at solid rock. Joe was shouting, Throw me up samples, boys, and studying bits of brown stone with a magnifying glass like a government geologist.

By four oclock even Joe had to admit that we hadnt found, an Eldorado. Its funny, he declared mournfully, Id have staked my life Id found the lode after digging out that gold I showed you. Still, it cant be helped. , You know what goldmining is. Either your lucks in or its out. This time its out. But what about our 30? growled Charlie the old gunner. Well, now. declared Joe. Fair go. You risked it knowingly and you lost it. He waved his hands in the air. Charlie looked hard at the waving hands and said a very rude word. Say, Shropper, he shouted, wheres that gold ring you used to wear? Joe went pale and muttered: I lost it a few days ago. You melted It down and stuck it in the rock, roared Charlie. Joe tried to bolt, but we collared him, administered summary justice, and from his belt took that which was our own. We let him keep our contracts.

By SMITHS STAFF REPORTER

Smith's Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1919 - 1950)

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

Another great story Jemba. Is it true that the Chinese gold buyers put a thin layer of honey on one set of scales and would re weigh it again on another set, thus keeping the small amount on the first set and paying on the second?

Mackka

Mackka

Jemba said:Your spot on Mackka, not only the Chinese but others as well, they all had a go at it. That practice was called a certain name but for the life of me, I just cant think of what it was called. ???

I've also read of gold buyers weighing fines, who ran their hands through their greasy hair or a well-oiled beard, before carefully raking the fines with their fingers 'to ensure that no stone was included' and so accumulated fine gold powder/dust in their hair/beard and on their hands for later careful washing and panning.

Yes what was the term for that practice?

Mackka

Mackka

I will know it when i hear it mate.

Mackka

Mackka

Dry-blowing for Gold

By JACKSON J. DOUGHTY

The lure of gold, some folk call it; but it is more than that it is the lure of living. Those who have never "chased the pennyweight with a dry-blowing machine in Western Australia cannot know the sense of peace and divine freedom that comes of warm, sunny days in the out-of-doors days spent in health-giving toil that is not work at all, but only a splendid game of hide-and-seek, with fortune ever within grasp but seldom quite caught up with; a winking, smiling, beckoning jade, luring one on, scattering clues in the shape of dull-gleaming gold specks that cause the eyes to sparkle and the pulses to quicken, and hint at dreams coming true in the next shovelful of wash dirt. It used to be known as "desert country, that vast fenceless tableland extending east of Southern Cross to Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie and beyond, and that term may still apply to it, for it is without rivers or creeks, and its lakes are salt, the source of its water-supply being Mundaring Weir, four hundred miles away!

Parallel with the railway that links up the outback with the closely populated coastal areas marches the Coolgardie Pipe Line, conveying a ceaseless flow of fresh water to the goldfields towns. Enough for human and animal consumption, enough to make gardens bloom and parks green and shady, enough to work the crushing mills that rumble night and day; but not enough to enable the alluvial gold seeker at work in some distant gum-clad gully or wide saltbush flat to employ a sluice box or a cradle after the methods followed by gold-hunters in other parts of the world. For him the dry panning, the shaker, and the "blower. But, scanty though the rainfall may be, though brown and grassless the ground between the blue-grey saltbush and the thorny desert plants, the panorama is none the less green a vast, billowing sea of vegetation, with tall gums rising out of the flats and dense thickets of smooth-barked gimlet saplings hugging the slopes; tea-trees scattering shade on the bare, iron stone knobs of miniature ranges; here a stretch of yellow sand dotted with dry tufts of spinifex grass that one knows better than to sit upon. Rough going in places for this old runabout truck of mine, with the spindly-framed dry-blower standing high beside the water drums, and the tucker boxes, mining gear and camp equipment rattling as we go! But there, on that long, narrow flat that comes sweeping out of the diorite hills, we shall dig a hole. The day is early yet; by noon we ought to bottom. It depends on the nature and depth of the ground, of course, but here in Western Australia "deep leads are the exception rather than the rule, and in the majority of cases the richest patches of gold have been found quite close to the surface. This flat The author and his dry-blower. may have ten or twelve feet of overburden covering the "country bottom; we may find some of the layers of soil tough picking, too; but theres no hurry. This little slip of stiffened paper called a Miners Right, which anybody can buy for five shillings from any mining registrar, enables me to go where I like, when and how I like, and take possession of any bit of ground that pleases my fancy simply by erecting four pegs at the corners of my claim. Once those stakes are in, I am undisputed owner of it mineral rights, timber rights, water rights, building rights, and every other right. I can give it away or sell it, or simply abandon it when ever I choose; but the King himself is powerless to put me off it if I wish to stay and work it.

But we are not going to trouble about pegging a claim on this fiat not yet. Time enough for that if we strike anything worth while. Now let us consider. It is a pretty safe bet that this was a nice sort of river about a million years ago. And it is quite on the cards that that ridge of schist, which forms one edge of the flat for some distance and carries a trace of gold all of its length, once rose up to ten or twenty times its present height and was possibly yellow with encrusted gold. Since then there have been earthquakes, sea-immersions, and all manner of changes. But what happened to the gold? Gold does not corrode or evaporate or get blown away. Gold remains. As the ridge wore away with the passage of time, the pieces of freed gold would slip gradually down the slope to the river, there to be washed against bars and into pockets, to lodge and remain while the river dried up and became this flat we are looking at. So we are not going to sink our hole in any haphazard fashion. We are going to see this flat as the river it might have been. We are going to watch the swirls and eddies, figure out the twists and turns, calculate the position of the likeliest channel or "gutter that the gold would be gradually swept into, and then we are going to do a lot of sweating to prove our theories. Fascinating work? You bet it is! here, give me that pick and I shall make a start. Once we get through this heavy, top loam that is baked hard with the sun, progress will be fairly rapid. This is typical West Australian goldfields soil, rich and red and deep. And so through the morning, with the hole deepening and the sun rising to its zenith. Lunch under the shade of a leafy salmon-gum, the smoke of a fire lazing up into the scintillating blue of mid-day, the languid hush broken by the raucous cry of a jay. And then back to work, deepening the hole, sinking through layer after layer of drift-wash and clay, until finally a heavier, stiffer gravel is reached the 'dinkum wash. There is a foot or more of this, and then the "bottom shows, pale green and softish, with smooth, water-washed undulations that please our professional eye. Interest quickens here. The wash-dirt is examined and pronounced fit to eat, the bottom is described as "beautiful. The latter might be seen to dip towards one end of the hole, an indication that the deepest part of the gutter has been missed. That fact, however, does not worry us. If the gutter carries gold, signs will be given in this parcel of "dirt. We shall unload the dry-blower and test our fortune. A bulky contrivance to lift out of the car, this, and one of sufficient delicacy to necessitate careful handling. But it is on the ground now. We shall stick the wheel in the sockets prepared and trundle it like a barrow over to the hole. Take the wheel out again and put it to one side, remove the sheet of tin protecting the ripple tray, and fill up the hopper with wash.

And now we are off! Shake, shake, shake, and with every push and pull of the handles the bellows are working, pumping blasts of air through the finely perforated bottom of the ripple tray, blowing the dust out of the sieved gravel that descends in a stream from the coarsely perforated hopper tray above, and slides slowly like an avalanche in miniature over the ripples, and so out to form a "tailing heap in front of the machine. Gold particles, by reason of their weight, resist the urge of the draught and remain caught in the ripples. In a little while, the magnificent heap of wash-dirt which we have worked so hard to obtain has passed through the machine and is clogging the "blower legs. Such gold as it might have contained is now resting among the gravel-filled ripples, or, if there be large nuggets, in the wide, shallow hopper tray, which, fed directly from the hopper itself, separates the The breeze blows the dust and finer particles of light gravel .. . but the gold and heavier stuff falls unerringly into the dish. larger stones from the gravel and throws them out over the front of the machine. But a search there reveals nothing that gleams with that never-forgotten dullness of gold. Remains then the ripple tray, narrow and long, which slides out from its bed on top of the bellows and is carefully emptied into one of the two dishes. Standing sideways to the breeze, then, and holding the filled dish high, one cants it gently so that its contents cascade into the other dish at ones feet. The breeze blows the dust and finer particles of light gravel out of the stream, but the gold and heavier stuff falls unerringly into the dish. The pans are reversed then, and the process continues until one is satisfied that no more clogging dust remains, and the real "panning off begins. Back bent now and the half-filled dish held knee high, both hands gripping its steel sides as it is shaken vigorously to make such gold as it may contain sink to the bottom! Then the dish is lightened by skimming off the top layer of dirt. Again the pan is shaken and swirled, and again it is lightened by skimming off another layer. And so to the end, when little remains and no more skimming can be done without the risk of losing its hoped-for gold. By working the dish with a rotary motion, the little that is left is coaxed into one side of the pan. The pan is lifted close to the face then, and softlyoh, so very softly!the residue of dirt is blown upon.

Ah! there shows a small gleaming "colour, stolidly resisting the power that compels the dirt to roll back; there shows another, and another! Hold these three with the finger tips of the left hand, jerk the dish slightly to throw the dirt more flatly across the bottom of the pan, and blow again. Whoa, there! Thats better! The others were "fly-specks, but here is a piece almost half an inch long. Not of much value, certainlywe doubt if it will weigh half a pennyweightbut it is an indication of possible riches not far away. Now which side of the hole did that piece come from? Hm, should have made two parcels of the wash and run them through separately. It might have come from the higher portion of the bottom, or more likely from the dipping corner. Well, all we can do is try both ends of the hole, put in a bit of a drive from that deepest side, perhaps, and cut right across the gutter. Or it may be that the rising side is merely an irregularity of the old river-bed; the bottom may dip again on that side? see, already the sun is near its setting, though it seems scarce an hour since we rose from lunch. We shall take a gun in search of rabbit or turkey, or perhaps a roo, returning as the shadows fade to kindle a fire of crackling boughs, knead and cook a johnny-cake, and eat heartily of our stores. And after wards we shall sit and smoke in the purpling dusk, while the gold and crimson of the afterglow fades and the stars commence looking down. From some distant ridge comes the cuckoo-like call of a mopoke; clear and far away sounds the lonely howl of a dingo; in a gimlet thicket near at hand a magpie flutters sleepily. And ever the twilight deepens and the glowing fire gleams redder, till at length a peaceful drowsiness steals over us and we wriggle happily into our blankets to sleep.

To-morrow Ah, who knows what to-morrow may bring. And therein lies the thrill of gold-hunting. Though the days and the months and the years slide by, though Fortune smiles and frowns by turns, there remains always, face downwards, a card to be shown - - - Ah to-morrow!

Walkabout.Vol. 1 No. 8 (1 June 1935)

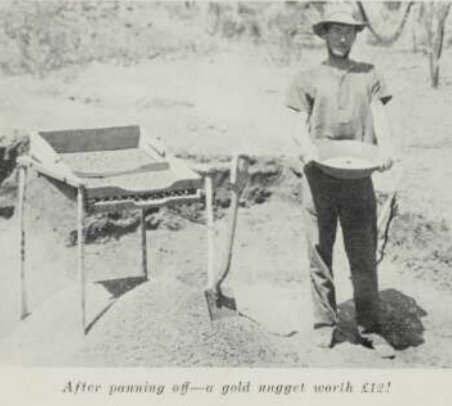

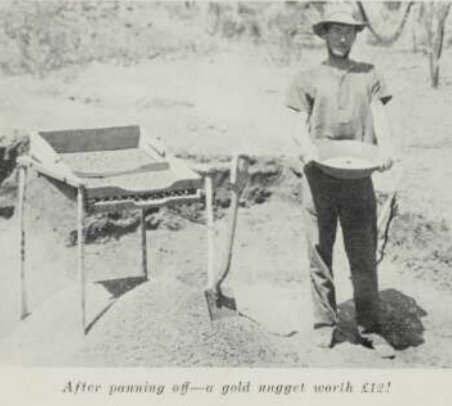

The Author and his dry-blower

https://nla.gov.au/nla

By JACKSON J. DOUGHTY

The lure of gold, some folk call it; but it is more than that it is the lure of living. Those who have never "chased the pennyweight with a dry-blowing machine in Western Australia cannot know the sense of peace and divine freedom that comes of warm, sunny days in the out-of-doors days spent in health-giving toil that is not work at all, but only a splendid game of hide-and-seek, with fortune ever within grasp but seldom quite caught up with; a winking, smiling, beckoning jade, luring one on, scattering clues in the shape of dull-gleaming gold specks that cause the eyes to sparkle and the pulses to quicken, and hint at dreams coming true in the next shovelful of wash dirt. It used to be known as "desert country, that vast fenceless tableland extending east of Southern Cross to Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie and beyond, and that term may still apply to it, for it is without rivers or creeks, and its lakes are salt, the source of its water-supply being Mundaring Weir, four hundred miles away!

Parallel with the railway that links up the outback with the closely populated coastal areas marches the Coolgardie Pipe Line, conveying a ceaseless flow of fresh water to the goldfields towns. Enough for human and animal consumption, enough to make gardens bloom and parks green and shady, enough to work the crushing mills that rumble night and day; but not enough to enable the alluvial gold seeker at work in some distant gum-clad gully or wide saltbush flat to employ a sluice box or a cradle after the methods followed by gold-hunters in other parts of the world. For him the dry panning, the shaker, and the "blower. But, scanty though the rainfall may be, though brown and grassless the ground between the blue-grey saltbush and the thorny desert plants, the panorama is none the less green a vast, billowing sea of vegetation, with tall gums rising out of the flats and dense thickets of smooth-barked gimlet saplings hugging the slopes; tea-trees scattering shade on the bare, iron stone knobs of miniature ranges; here a stretch of yellow sand dotted with dry tufts of spinifex grass that one knows better than to sit upon. Rough going in places for this old runabout truck of mine, with the spindly-framed dry-blower standing high beside the water drums, and the tucker boxes, mining gear and camp equipment rattling as we go! But there, on that long, narrow flat that comes sweeping out of the diorite hills, we shall dig a hole. The day is early yet; by noon we ought to bottom. It depends on the nature and depth of the ground, of course, but here in Western Australia "deep leads are the exception rather than the rule, and in the majority of cases the richest patches of gold have been found quite close to the surface. This flat The author and his dry-blower. may have ten or twelve feet of overburden covering the "country bottom; we may find some of the layers of soil tough picking, too; but theres no hurry. This little slip of stiffened paper called a Miners Right, which anybody can buy for five shillings from any mining registrar, enables me to go where I like, when and how I like, and take possession of any bit of ground that pleases my fancy simply by erecting four pegs at the corners of my claim. Once those stakes are in, I am undisputed owner of it mineral rights, timber rights, water rights, building rights, and every other right. I can give it away or sell it, or simply abandon it when ever I choose; but the King himself is powerless to put me off it if I wish to stay and work it.

But we are not going to trouble about pegging a claim on this fiat not yet. Time enough for that if we strike anything worth while. Now let us consider. It is a pretty safe bet that this was a nice sort of river about a million years ago. And it is quite on the cards that that ridge of schist, which forms one edge of the flat for some distance and carries a trace of gold all of its length, once rose up to ten or twenty times its present height and was possibly yellow with encrusted gold. Since then there have been earthquakes, sea-immersions, and all manner of changes. But what happened to the gold? Gold does not corrode or evaporate or get blown away. Gold remains. As the ridge wore away with the passage of time, the pieces of freed gold would slip gradually down the slope to the river, there to be washed against bars and into pockets, to lodge and remain while the river dried up and became this flat we are looking at. So we are not going to sink our hole in any haphazard fashion. We are going to see this flat as the river it might have been. We are going to watch the swirls and eddies, figure out the twists and turns, calculate the position of the likeliest channel or "gutter that the gold would be gradually swept into, and then we are going to do a lot of sweating to prove our theories. Fascinating work? You bet it is! here, give me that pick and I shall make a start. Once we get through this heavy, top loam that is baked hard with the sun, progress will be fairly rapid. This is typical West Australian goldfields soil, rich and red and deep. And so through the morning, with the hole deepening and the sun rising to its zenith. Lunch under the shade of a leafy salmon-gum, the smoke of a fire lazing up into the scintillating blue of mid-day, the languid hush broken by the raucous cry of a jay. And then back to work, deepening the hole, sinking through layer after layer of drift-wash and clay, until finally a heavier, stiffer gravel is reached the 'dinkum wash. There is a foot or more of this, and then the "bottom shows, pale green and softish, with smooth, water-washed undulations that please our professional eye. Interest quickens here. The wash-dirt is examined and pronounced fit to eat, the bottom is described as "beautiful. The latter might be seen to dip towards one end of the hole, an indication that the deepest part of the gutter has been missed. That fact, however, does not worry us. If the gutter carries gold, signs will be given in this parcel of "dirt. We shall unload the dry-blower and test our fortune. A bulky contrivance to lift out of the car, this, and one of sufficient delicacy to necessitate careful handling. But it is on the ground now. We shall stick the wheel in the sockets prepared and trundle it like a barrow over to the hole. Take the wheel out again and put it to one side, remove the sheet of tin protecting the ripple tray, and fill up the hopper with wash.

And now we are off! Shake, shake, shake, and with every push and pull of the handles the bellows are working, pumping blasts of air through the finely perforated bottom of the ripple tray, blowing the dust out of the sieved gravel that descends in a stream from the coarsely perforated hopper tray above, and slides slowly like an avalanche in miniature over the ripples, and so out to form a "tailing heap in front of the machine. Gold particles, by reason of their weight, resist the urge of the draught and remain caught in the ripples. In a little while, the magnificent heap of wash-dirt which we have worked so hard to obtain has passed through the machine and is clogging the "blower legs. Such gold as it might have contained is now resting among the gravel-filled ripples, or, if there be large nuggets, in the wide, shallow hopper tray, which, fed directly from the hopper itself, separates the The breeze blows the dust and finer particles of light gravel .. . but the gold and heavier stuff falls unerringly into the dish. larger stones from the gravel and throws them out over the front of the machine. But a search there reveals nothing that gleams with that never-forgotten dullness of gold. Remains then the ripple tray, narrow and long, which slides out from its bed on top of the bellows and is carefully emptied into one of the two dishes. Standing sideways to the breeze, then, and holding the filled dish high, one cants it gently so that its contents cascade into the other dish at ones feet. The breeze blows the dust and finer particles of light gravel out of the stream, but the gold and heavier stuff falls unerringly into the dish. The pans are reversed then, and the process continues until one is satisfied that no more clogging dust remains, and the real "panning off begins. Back bent now and the half-filled dish held knee high, both hands gripping its steel sides as it is shaken vigorously to make such gold as it may contain sink to the bottom! Then the dish is lightened by skimming off the top layer of dirt. Again the pan is shaken and swirled, and again it is lightened by skimming off another layer. And so to the end, when little remains and no more skimming can be done without the risk of losing its hoped-for gold. By working the dish with a rotary motion, the little that is left is coaxed into one side of the pan. The pan is lifted close to the face then, and softlyoh, so very softly!the residue of dirt is blown upon.

Ah! there shows a small gleaming "colour, stolidly resisting the power that compels the dirt to roll back; there shows another, and another! Hold these three with the finger tips of the left hand, jerk the dish slightly to throw the dirt more flatly across the bottom of the pan, and blow again. Whoa, there! Thats better! The others were "fly-specks, but here is a piece almost half an inch long. Not of much value, certainlywe doubt if it will weigh half a pennyweightbut it is an indication of possible riches not far away. Now which side of the hole did that piece come from? Hm, should have made two parcels of the wash and run them through separately. It might have come from the higher portion of the bottom, or more likely from the dipping corner. Well, all we can do is try both ends of the hole, put in a bit of a drive from that deepest side, perhaps, and cut right across the gutter. Or it may be that the rising side is merely an irregularity of the old river-bed; the bottom may dip again on that side? see, already the sun is near its setting, though it seems scarce an hour since we rose from lunch. We shall take a gun in search of rabbit or turkey, or perhaps a roo, returning as the shadows fade to kindle a fire of crackling boughs, knead and cook a johnny-cake, and eat heartily of our stores. And after wards we shall sit and smoke in the purpling dusk, while the gold and crimson of the afterglow fades and the stars commence looking down. From some distant ridge comes the cuckoo-like call of a mopoke; clear and far away sounds the lonely howl of a dingo; in a gimlet thicket near at hand a magpie flutters sleepily. And ever the twilight deepens and the glowing fire gleams redder, till at length a peaceful drowsiness steals over us and we wriggle happily into our blankets to sleep.

To-morrow Ah, who knows what to-morrow may bring. And therein lies the thrill of gold-hunting. Though the days and the months and the years slide by, though Fortune smiles and frowns by turns, there remains always, face downwards, a card to be shown - - - Ah to-morrow!

Walkabout.Vol. 1 No. 8 (1 June 1935)

The Author and his dry-blower

https://nla.gov.au/nla

Reminiscences OF A GOLD-DIGGER.

[From the S. M. HERALD.]

ON the: gold-fields, some few years ago, when the claims were much smaller than those allowed now, in consequence of the richness of the ground, scarcely a day passed but there were several disputes, and the commissioner was summoned to decide them, for at that time his decision was final, there being no local courts or mining boards as. there is at the present time. At the appearance of the commissioner, always on horseback with one of the mounted police as orderly, it was a signal for a rush of diggers tea claim in dispute, to hear the pros and cons, and pass remarks on the decision of the commissioner. Towards noon, one. day, the cry of Joe passed along the lead I was working onfor at the sight. of a single policeman it was always thought there was to be a digger hunt, that is, a search for licenses, and they scarce had entered a gully before Joe was cried from one end to the other, and all those who were not in the possession of licenses either took to the bush or got down holes into drives to get out of the way, and so avoid a fine of 5 or imprisonment. In the claim I was working there was one long drive, or what, was considered a long drive in those days, and in a very few minutes some seven or eight men rushed up and taking hold of the rope, descended, well knowing that I had a license, and that on showing it to the policeman, it would, in a measure, satisfy him, for he no more dare descend a diggers claim than he would attempt to fly-however great a suspicion he might have of there being diggers below. Happily these scenes have passed away, and digger hunts are only known of by the old diggers, or, as it is now the fashion to call them, gold miners. Without entering into the justice or policy of this tax, the means necessarily adopted for the collection of it appeared to be so despotic and repugnant to Englishmen, that a feeling of animosity and hatred was always felt and expressed towards the authorities; Nor was it surprising when it is considered that a large body of mounted and foot police all armed, used to perambulate the different. diggings once or twice a month, who, possessed of a little brief authority, used, with very few exceptions, to demand to see the licenses of men in no very polite terms, and take those in charge that could not produce them, place them between a troop of armed men, match them to the camp, the bulk of whom were guilty of one offence-poverty-that dissatisfaction and resistance should be shown can surprise no one The only surprise is, that more open resistance was not made; but that innate respect for the law when administered by Englishmen, although for a time despotic, was fully exemplified in these times, but with the increase of population, and the difficulty of all finding gold (for in the best days of digging there was always far greater number of unlucky diggers).

Instead of endeavoring to conciliate the diggers, the late lamented Sir Chiarloa ? lotham adopted the quarter-deck policy he had been so long used to, and issued. Orders to the various commissioners to increase these digger hunts ; so that the diggers were always being harassed by the police. The policy eventually led to the Eureka Stockade, and riots at Ballarat, and the lamentable sacrifice of life, the proclamation of martial law, and the impossibility of getting jury of Englishmen to convict their fellowmen of any offence, after being goaded on to desperation. It is true they succeeded in establishing the supremacy of the law, only to acknowledge it was untenable, and that diggers were men, and had grievances, and by adopting a course of reason and justice, soon conciliated them. But on the Administrative power exercised in those days in Victoria, an indelible stain rests, and it will be very many years before that mistaken policy, and the butchery at the Eureka Stockade will cease to be spoken of, and history will hereafter point to it as a warning to those in possession of power of the great responsibility entrusted in their keeping, and the necessity of exercising it with discretion and mercy. But I am forgetting the disputed claim. When it was found it was only the commissioner to settle a dispute, the diggers left their-various hiding places, and a very formidable crowd soon collected. It would be impossible to convey a correct idea of the dispute; one party showed their pegs, pointed out the boundary of the claim; the other party as stoutly claimed them as being theirs; witnesses were brought on either side to state that they had seen each of the contending parties place the pegs, in; others that they had left the claim a day-for at this time any claim that was left four and twenty hours could be jumped, that is, any other. party could go into it. The commissioners had to be possessed of the greatest amount of patience, and to use their own judgment in the majority of cases, for the evidence given was generally so conflicting and contradictory that it was impossible to decide upon it,-and it must be admitted their decisions were generally considered correct, but once decided there was no appeal; an ad vantage, and a very great one, certainly not possessed under the present mining regulations.

After the decision, and the usual amount of threatening by the losing party of what they were going to do to the winning party, the crowd soon dispersed, knowing the men that had gained the claims, I spoke and said, Well, Walter, what sort of a claim have you got ? Pretty decent, H- , he replied; I am just going to wash a tub; come and look at it. And making our way some little distance from the claim to where he was washing, from about four buckets of dirt lie got some twenty ounces of gold. Why, you have a pile hole, I exclaimed; ? he is working with you? Only Jim an Sam, he replied; if it only continues like this I shall go home and astonish some of my friends. I hope it may, I replied, and returned to my own claim. James and Walter B- were brothers, and Samuel K--- was a cousin of theirs; they had been digging some time-but this was the first golden hole they had got. They were all respectable young men, and until their arrival on the gold-field, never knew what manual labor was; but a stranger would never suppose they were relatives. James, the elder, was a determined, self-willed fellow, who must always have his own way-ever complaining and quarrelling with his brother. Walter was quite the reverse very quite and gentlemanly, constantly making excuses for James, and endeavoring to reason with him, but it seemed that he could not brook being spoken to-with that imperious temper, he considered his word was low, and although I believe lie had the greatest respect for his brother, his temper was such that he could not restrain himself.

After they had been working some few weeks, one Saturday, I went to their tent to learn how they had been doing. Walter showed me escort receipts for upwards of five hundred ounces of gold. Well, Walter, I said, you have been doing a stroke. Do you mean to toll me that that is your share ; for I noticed all the receipts were made out in his name only. Oh, no, he replied, this is Jims and mine. Well, he is a curious fellow, I replied; he is always quarrelling and calling you anything but a gentleman, and yet he leaves between two and three hundred ounces of gold in your hands. Oh, you do! not know Jim H---, he re plied: he does not mean what he says half his time, and when he gets in a passion he does-not know what he says. The first hundred ounces I deposited, I wanted him to come up with me and put fifty ounces in his own name; but lie got in a passion and asked me if I thought he was afraid of my robbing him, so that I have always deposited it in my own name. Next week I expect will finish the claim, if so, we shall go down to Melbourne and go home. Sam will go with you I suppose, I said. Well, I expect he will ; but he is getting rid of a- deal of gold, if he does go home, I dont think he will have much more than a hundred ounces to take with him. I was about leaving when Jim entered, and a general conversation ensued with respect to the claim, and as a matter of course a dispute ; Walter wanting Jim to put in some props to keep up the ground while they took out the last block, saying it was not safe, and Jim swearing that lie would not put any props in for it did-not require them, and taunting Walter with being afraid to work under ground., Walter made a few remarks; to which he replied, Well, if I am smothered, you have taken good care of the gold, so-you have no occasion to complain. Walter could scarce reply; he tried to hide his emotions, and at last said: Jim, I make every allowance I possibly can for you, and you should be the last to make such a remark. Come up to the Commissioners, and I will transfer your share. How many times have I asked you? but you. always refuse. I think you must be taking leave of your senses. In the Commissioners, he said, striking his hand violently on the table. I dare you to rob me of a single penny.

He was getting very excited, and I left; and, from his appearance, I was inclined to go farther than Walter, for I was of opinion he had quite lost his reason. I saw Walter the next day, and told him what I thought, and asked him if he drank; he replied that he never touched liquor, that it: was only his nervous and passionate way-that he was all right then; but that ever since he had a fall from a horse some four years previously, his temper and disp6sition was completely changed. One day early in the following week I was at my own claim when Walter passed carrying two props. so you are going to put some more timber in after all, I cried out. Oh, yes, he replied; Sam says he will not work below without we do and Jim. swears they - shall not go in, so that Sam and I will have a. rare fight. There is only one little block, supporting near one half of the claim; I would not work under it for all the gold in the gully, and away he went. It was about ten oclock in the. morning, and the majority of diggers were on the top, for it was smoke 0 ! that is a short spell, and a few draws of the pipe. In a few minutes there was a general rush to Walters claim. I went also, with a sort of presentiment that the ground had fallen in; nor was I mistaken. On Walter arriving at the shaft with the props, he called out, and getting no answer, looked down ; one side had caved in. He gave the alarm, and a general rush took place to the claim; two men descended, and, after a deal of trouble, succeeded in extricating Sam, who was almost smothered; he was badly crushed, and one of his arms broken. . We learnt from him that Jim was some twenty feet away from the shaft, and that the whole of the ground had fallen in.. In a very few minutes some score of diggers were engaged with pick and shovel, sinking a large hole, in the hopes that they would be enabled to save him. Being a question of life and death, all worked with astonishing determination. Men stood around eager to relieve them. After a few minutes of the hardest work, and in an in credibly short time, they succeeded in finding him, but alas, his career was finished; with his pick tightly grasped in one hand, his head pressed down to his feet (for when working he was sitting down, his legs under him); his back was broken, and he was so completely crushed and smothered, that his death must have been almost instantaneous. -Near him was a pannikin he always took down the shaft to put any small nuggets in that he might come across in knocking down the wash dirt. It contained some two or three ounces of gold. In one hand he held a small nugget of a few pennyweights, which he seemed to have been in the act of putting into the pannikin when the ground fell and crushed him to death. His remains were interred the next day, and Walter and Sam soon left for Melbourne.

About six years afterwards, whilst making some inquiries of the driver of a conveyance in which I was travelling, I was surprised on discovering him to be no other than Samuel K- . He told me that Walter had gone home, and that he knew nothing with respect to him. There was a letter advertised in the Melbourne list, he continued, for me, but I did not see it until some months after, and I never applied for it, for I had got rid of my gold, and could not send home any good news; so that I expect they think I am dead; and perhaps it is quite as well, for my poor old mother, if she is alive, would be but little gratified to find that her favorite son in this land of gold was driving a conveyance for his living.

J. A. H.

Examiner (Kiama, NSW : 1859 - 1862)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/102519946

http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/26007

[From the S. M. HERALD.]

ON the: gold-fields, some few years ago, when the claims were much smaller than those allowed now, in consequence of the richness of the ground, scarcely a day passed but there were several disputes, and the commissioner was summoned to decide them, for at that time his decision was final, there being no local courts or mining boards as. there is at the present time. At the appearance of the commissioner, always on horseback with one of the mounted police as orderly, it was a signal for a rush of diggers tea claim in dispute, to hear the pros and cons, and pass remarks on the decision of the commissioner. Towards noon, one. day, the cry of Joe passed along the lead I was working onfor at the sight. of a single policeman it was always thought there was to be a digger hunt, that is, a search for licenses, and they scarce had entered a gully before Joe was cried from one end to the other, and all those who were not in the possession of licenses either took to the bush or got down holes into drives to get out of the way, and so avoid a fine of 5 or imprisonment. In the claim I was working there was one long drive, or what, was considered a long drive in those days, and in a very few minutes some seven or eight men rushed up and taking hold of the rope, descended, well knowing that I had a license, and that on showing it to the policeman, it would, in a measure, satisfy him, for he no more dare descend a diggers claim than he would attempt to fly-however great a suspicion he might have of there being diggers below. Happily these scenes have passed away, and digger hunts are only known of by the old diggers, or, as it is now the fashion to call them, gold miners. Without entering into the justice or policy of this tax, the means necessarily adopted for the collection of it appeared to be so despotic and repugnant to Englishmen, that a feeling of animosity and hatred was always felt and expressed towards the authorities; Nor was it surprising when it is considered that a large body of mounted and foot police all armed, used to perambulate the different. diggings once or twice a month, who, possessed of a little brief authority, used, with very few exceptions, to demand to see the licenses of men in no very polite terms, and take those in charge that could not produce them, place them between a troop of armed men, match them to the camp, the bulk of whom were guilty of one offence-poverty-that dissatisfaction and resistance should be shown can surprise no one The only surprise is, that more open resistance was not made; but that innate respect for the law when administered by Englishmen, although for a time despotic, was fully exemplified in these times, but with the increase of population, and the difficulty of all finding gold (for in the best days of digging there was always far greater number of unlucky diggers).

Instead of endeavoring to conciliate the diggers, the late lamented Sir Chiarloa ? lotham adopted the quarter-deck policy he had been so long used to, and issued. Orders to the various commissioners to increase these digger hunts ; so that the diggers were always being harassed by the police. The policy eventually led to the Eureka Stockade, and riots at Ballarat, and the lamentable sacrifice of life, the proclamation of martial law, and the impossibility of getting jury of Englishmen to convict their fellowmen of any offence, after being goaded on to desperation. It is true they succeeded in establishing the supremacy of the law, only to acknowledge it was untenable, and that diggers were men, and had grievances, and by adopting a course of reason and justice, soon conciliated them. But on the Administrative power exercised in those days in Victoria, an indelible stain rests, and it will be very many years before that mistaken policy, and the butchery at the Eureka Stockade will cease to be spoken of, and history will hereafter point to it as a warning to those in possession of power of the great responsibility entrusted in their keeping, and the necessity of exercising it with discretion and mercy. But I am forgetting the disputed claim. When it was found it was only the commissioner to settle a dispute, the diggers left their-various hiding places, and a very formidable crowd soon collected. It would be impossible to convey a correct idea of the dispute; one party showed their pegs, pointed out the boundary of the claim; the other party as stoutly claimed them as being theirs; witnesses were brought on either side to state that they had seen each of the contending parties place the pegs, in; others that they had left the claim a day-for at this time any claim that was left four and twenty hours could be jumped, that is, any other. party could go into it. The commissioners had to be possessed of the greatest amount of patience, and to use their own judgment in the majority of cases, for the evidence given was generally so conflicting and contradictory that it was impossible to decide upon it,-and it must be admitted their decisions were generally considered correct, but once decided there was no appeal; an ad vantage, and a very great one, certainly not possessed under the present mining regulations.

After the decision, and the usual amount of threatening by the losing party of what they were going to do to the winning party, the crowd soon dispersed, knowing the men that had gained the claims, I spoke and said, Well, Walter, what sort of a claim have you got ? Pretty decent, H- , he replied; I am just going to wash a tub; come and look at it. And making our way some little distance from the claim to where he was washing, from about four buckets of dirt lie got some twenty ounces of gold. Why, you have a pile hole, I exclaimed; ? he is working with you? Only Jim an Sam, he replied; if it only continues like this I shall go home and astonish some of my friends. I hope it may, I replied, and returned to my own claim. James and Walter B- were brothers, and Samuel K--- was a cousin of theirs; they had been digging some time-but this was the first golden hole they had got. They were all respectable young men, and until their arrival on the gold-field, never knew what manual labor was; but a stranger would never suppose they were relatives. James, the elder, was a determined, self-willed fellow, who must always have his own way-ever complaining and quarrelling with his brother. Walter was quite the reverse very quite and gentlemanly, constantly making excuses for James, and endeavoring to reason with him, but it seemed that he could not brook being spoken to-with that imperious temper, he considered his word was low, and although I believe lie had the greatest respect for his brother, his temper was such that he could not restrain himself.

After they had been working some few weeks, one Saturday, I went to their tent to learn how they had been doing. Walter showed me escort receipts for upwards of five hundred ounces of gold. Well, Walter, I said, you have been doing a stroke. Do you mean to toll me that that is your share ; for I noticed all the receipts were made out in his name only. Oh, no, he replied, this is Jims and mine. Well, he is a curious fellow, I replied; he is always quarrelling and calling you anything but a gentleman, and yet he leaves between two and three hundred ounces of gold in your hands. Oh, you do! not know Jim H---, he re plied: he does not mean what he says half his time, and when he gets in a passion he does-not know what he says. The first hundred ounces I deposited, I wanted him to come up with me and put fifty ounces in his own name; but lie got in a passion and asked me if I thought he was afraid of my robbing him, so that I have always deposited it in my own name. Next week I expect will finish the claim, if so, we shall go down to Melbourne and go home. Sam will go with you I suppose, I said. Well, I expect he will ; but he is getting rid of a- deal of gold, if he does go home, I dont think he will have much more than a hundred ounces to take with him. I was about leaving when Jim entered, and a general conversation ensued with respect to the claim, and as a matter of course a dispute ; Walter wanting Jim to put in some props to keep up the ground while they took out the last block, saying it was not safe, and Jim swearing that lie would not put any props in for it did-not require them, and taunting Walter with being afraid to work under ground., Walter made a few remarks; to which he replied, Well, if I am smothered, you have taken good care of the gold, so-you have no occasion to complain. Walter could scarce reply; he tried to hide his emotions, and at last said: Jim, I make every allowance I possibly can for you, and you should be the last to make such a remark. Come up to the Commissioners, and I will transfer your share. How many times have I asked you? but you. always refuse. I think you must be taking leave of your senses. In the Commissioners, he said, striking his hand violently on the table. I dare you to rob me of a single penny.

He was getting very excited, and I left; and, from his appearance, I was inclined to go farther than Walter, for I was of opinion he had quite lost his reason. I saw Walter the next day, and told him what I thought, and asked him if he drank; he replied that he never touched liquor, that it: was only his nervous and passionate way-that he was all right then; but that ever since he had a fall from a horse some four years previously, his temper and disp6sition was completely changed. One day early in the following week I was at my own claim when Walter passed carrying two props. so you are going to put some more timber in after all, I cried out. Oh, yes, he replied; Sam says he will not work below without we do and Jim. swears they - shall not go in, so that Sam and I will have a. rare fight. There is only one little block, supporting near one half of the claim; I would not work under it for all the gold in the gully, and away he went. It was about ten oclock in the. morning, and the majority of diggers were on the top, for it was smoke 0 ! that is a short spell, and a few draws of the pipe. In a few minutes there was a general rush to Walters claim. I went also, with a sort of presentiment that the ground had fallen in; nor was I mistaken. On Walter arriving at the shaft with the props, he called out, and getting no answer, looked down ; one side had caved in. He gave the alarm, and a general rush took place to the claim; two men descended, and, after a deal of trouble, succeeded in extricating Sam, who was almost smothered; he was badly crushed, and one of his arms broken. . We learnt from him that Jim was some twenty feet away from the shaft, and that the whole of the ground had fallen in.. In a very few minutes some score of diggers were engaged with pick and shovel, sinking a large hole, in the hopes that they would be enabled to save him. Being a question of life and death, all worked with astonishing determination. Men stood around eager to relieve them. After a few minutes of the hardest work, and in an in credibly short time, they succeeded in finding him, but alas, his career was finished; with his pick tightly grasped in one hand, his head pressed down to his feet (for when working he was sitting down, his legs under him); his back was broken, and he was so completely crushed and smothered, that his death must have been almost instantaneous. -Near him was a pannikin he always took down the shaft to put any small nuggets in that he might come across in knocking down the wash dirt. It contained some two or three ounces of gold. In one hand he held a small nugget of a few pennyweights, which he seemed to have been in the act of putting into the pannikin when the ground fell and crushed him to death. His remains were interred the next day, and Walter and Sam soon left for Melbourne.

About six years afterwards, whilst making some inquiries of the driver of a conveyance in which I was travelling, I was surprised on discovering him to be no other than Samuel K- . He told me that Walter had gone home, and that he knew nothing with respect to him. There was a letter advertised in the Melbourne list, he continued, for me, but I did not see it until some months after, and I never applied for it, for I had got rid of my gold, and could not send home any good news; so that I expect they think I am dead; and perhaps it is quite as well, for my poor old mother, if she is alive, would be but little gratified to find that her favorite son in this land of gold was driving a conveyance for his living.

J. A. H.

Examiner (Kiama, NSW : 1859 - 1862)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/102519946

http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/26007

HINTS TO PROSPECTORS.

Gold Is Where You Find It.

DEAR "John,"-Allow me to give a little advise to the uninitiated or unexperienced prospector. He -need not study geology. All ' that is required is plenty of luck and he must be a thorough optimist, fond of walking and must never get tired of breaking stones. If he has luck he may go blindfolded, get bushed' and his horse may kick him or his foot may kick against a stone that has gold in it. Some good shows have been discovered that way. No doubt hick is a, great asset in most everything, particularly so in prospecting for gold.

There have been men who have never been outside of a town or away from a farm, have gone, to the fields not knowing one stone from another and have found a -good show. Within a few months they were looked upon as being great authorities on gold ore, geological ! formations and have blossomed out into what was generally' called mining experts. Coming back to town they were sought out for their opinion or advice. They were introduced everywhere as the men who found such and such a show and disposed of it at a really high figure, even speculators took them in.

Therefore, prospectors, I can tell you that you never know how' far you can get by simply following the. game. Many have taken it on and never left off until they struck it rich or died. 'Some of them are still going on the outback fields. It is a very fascinating game! you never know when and how you strike it, there- fore never, be idle. If you go prospecting let it be alluvial or reefing. If the latter, 'go anywhere. Keep any stone be it white, black or otherwise and have a good look at it. You may see spots. All that glitters is not gold. Dolly the stones and if there are any prospects , look for more:

If you find anything to work on start on your best looking spot. Put in a costeen, that is a trench, across the country east to west as most of the reefs or lodes strike a northerly and southerly direction. Very few east to west carry gold. If you strike a reasonable or good show the experts can tell you their opinions and all the technical terms of rocks and they will be able to tell you where gold would be most prevalent. They will look wise and will tell you that you will have to do more work. They will put the compass on it and tell you how the lode or reef is bearing and when they see your prospects they will tell you to get an assay taken to make sure. I can tell you that : these experts are really clever once you find the gold. If you do not strike it rich keep on knapping more stones.

If you are looking for alluvial-that is free gold laying about in the soil or other- wise-look first at every little water- course in a dip or little basin or on a bend and if you locate fine gold go further up as the gold at the source is always coarser, (not as someone who issued a book on prospecting had told his readers to go down hill for the coarser gold). If the gold by the agency of water, eruption or wholesale movement, found its. way more into flat country there is more or less what is called a deep lead. The further you go out from the source the deeper you have to sink to where the deposit occurred or to the bottom of the lead. Again if you are lucky you may make good and strike - it in your first shaft or hole, but if the lead strikes a bar or stronger cross course it may turn off into somebody else's ground. If the ground around you is hot taken by others you an drive or crosscut down below or sink another shaft. If you strike it first go you can tell others that it was your judgment and you can again become an expert.

I give all the foregoing information free and let me tell you there are hundreds of thousands of ounces of alluvial gold buried about Kalgoorlie alone for you or the experts to practice on. Be an optimist and have good luck but you have to Work and work hard.

GUS LUCK, Victoria Park.

P.S.-In sinking, driving or any other work on. reef or lode formation or for alluvial, whenever possible scratch up the fines on the floor and pan that off. If you do not get any gold prospects in that there is not much in the lode. etc. Alluvial scrapings should be left in air for some time.-G.I.

Western Mail

May 1941

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

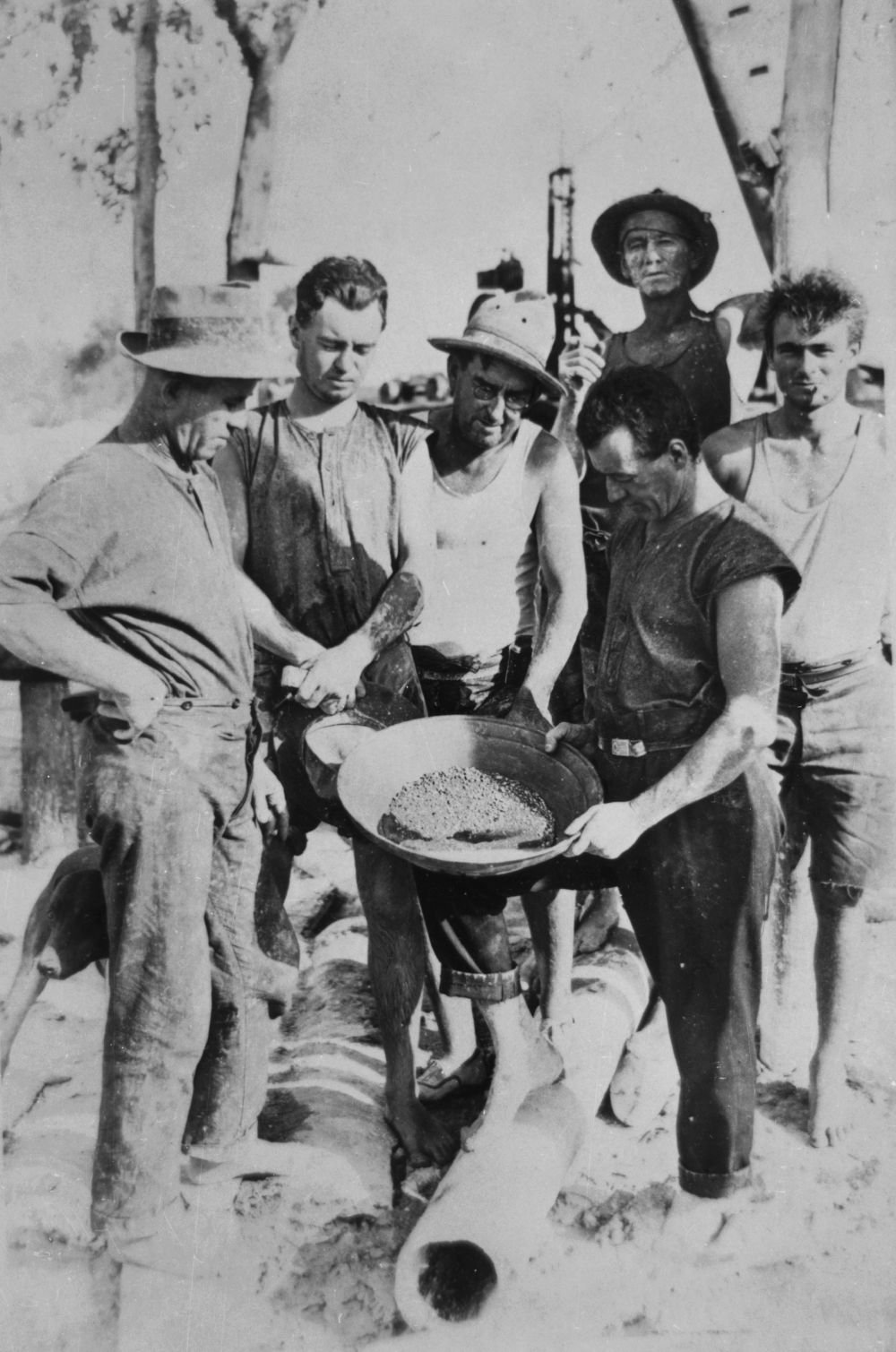

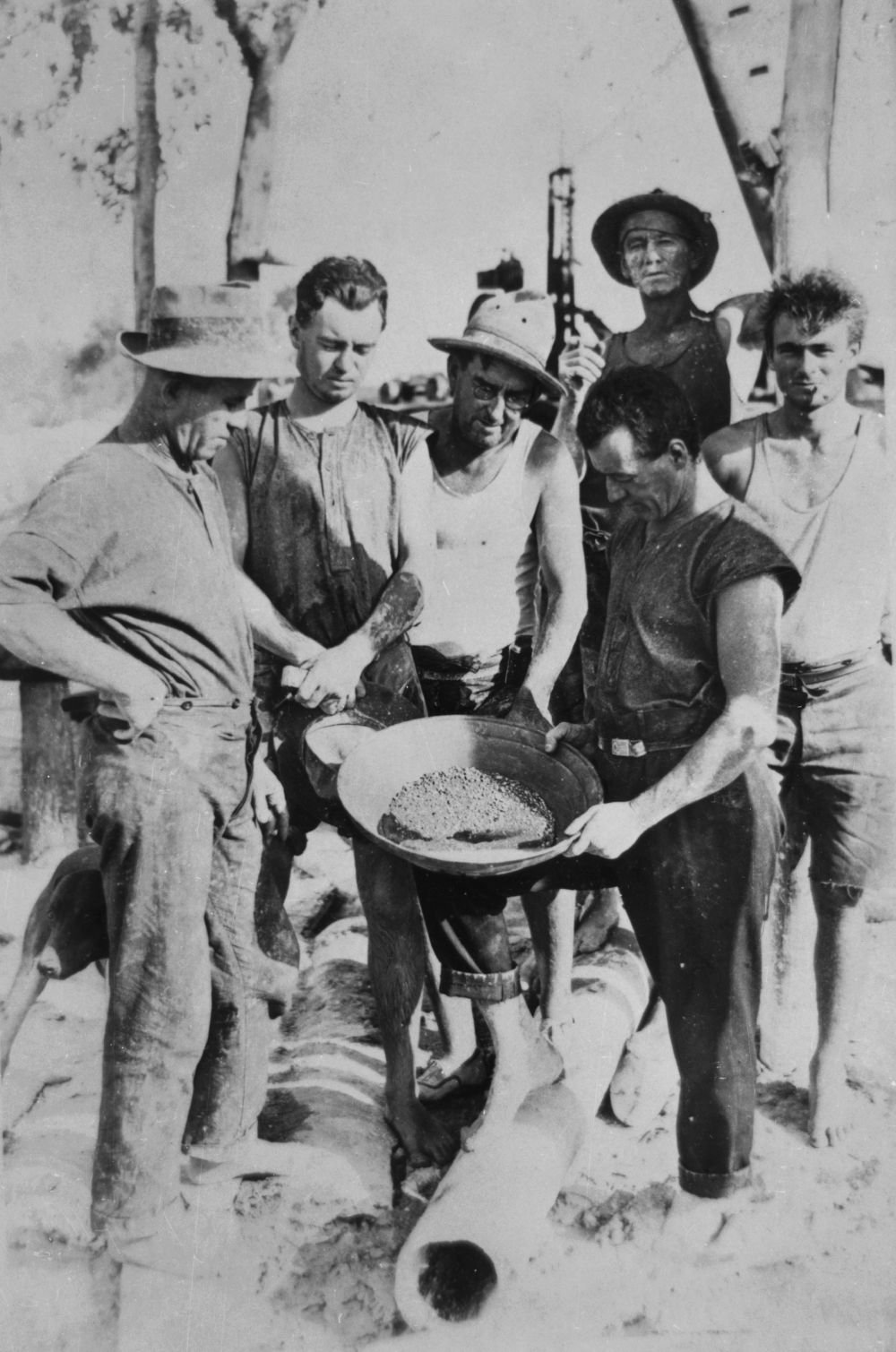

Prospectors panning for gold at Wenlock, Queensland, ca. 1930

https://digital.slq.qld.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?change_lng=en&dps_pid=IE289734

Gold Is Where You Find It.

DEAR "John,"-Allow me to give a little advise to the uninitiated or unexperienced prospector. He -need not study geology. All ' that is required is plenty of luck and he must be a thorough optimist, fond of walking and must never get tired of breaking stones. If he has luck he may go blindfolded, get bushed' and his horse may kick him or his foot may kick against a stone that has gold in it. Some good shows have been discovered that way. No doubt hick is a, great asset in most everything, particularly so in prospecting for gold.

There have been men who have never been outside of a town or away from a farm, have gone, to the fields not knowing one stone from another and have found a -good show. Within a few months they were looked upon as being great authorities on gold ore, geological ! formations and have blossomed out into what was generally' called mining experts. Coming back to town they were sought out for their opinion or advice. They were introduced everywhere as the men who found such and such a show and disposed of it at a really high figure, even speculators took them in.

Therefore, prospectors, I can tell you that you never know how' far you can get by simply following the. game. Many have taken it on and never left off until they struck it rich or died. 'Some of them are still going on the outback fields. It is a very fascinating game! you never know when and how you strike it, there- fore never, be idle. If you go prospecting let it be alluvial or reefing. If the latter, 'go anywhere. Keep any stone be it white, black or otherwise and have a good look at it. You may see spots. All that glitters is not gold. Dolly the stones and if there are any prospects , look for more:

If you find anything to work on start on your best looking spot. Put in a costeen, that is a trench, across the country east to west as most of the reefs or lodes strike a northerly and southerly direction. Very few east to west carry gold. If you strike a reasonable or good show the experts can tell you their opinions and all the technical terms of rocks and they will be able to tell you where gold would be most prevalent. They will look wise and will tell you that you will have to do more work. They will put the compass on it and tell you how the lode or reef is bearing and when they see your prospects they will tell you to get an assay taken to make sure. I can tell you that : these experts are really clever once you find the gold. If you do not strike it rich keep on knapping more stones.

If you are looking for alluvial-that is free gold laying about in the soil or other- wise-look first at every little water- course in a dip or little basin or on a bend and if you locate fine gold go further up as the gold at the source is always coarser, (not as someone who issued a book on prospecting had told his readers to go down hill for the coarser gold). If the gold by the agency of water, eruption or wholesale movement, found its. way more into flat country there is more or less what is called a deep lead. The further you go out from the source the deeper you have to sink to where the deposit occurred or to the bottom of the lead. Again if you are lucky you may make good and strike - it in your first shaft or hole, but if the lead strikes a bar or stronger cross course it may turn off into somebody else's ground. If the ground around you is hot taken by others you an drive or crosscut down below or sink another shaft. If you strike it first go you can tell others that it was your judgment and you can again become an expert.

I give all the foregoing information free and let me tell you there are hundreds of thousands of ounces of alluvial gold buried about Kalgoorlie alone for you or the experts to practice on. Be an optimist and have good luck but you have to Work and work hard.

GUS LUCK, Victoria Park.

P.S.-In sinking, driving or any other work on. reef or lode formation or for alluvial, whenever possible scratch up the fines on the floor and pan that off. If you do not get any gold prospects in that there is not much in the lode. etc. Alluvial scrapings should be left in air for some time.-G.I.

Western Mail

May 1941

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/

Prospectors panning for gold at Wenlock, Queensland, ca. 1930

https://digital.slq.qld.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?change_lng=en&dps_pid=IE289734

- Joined

- Nov 16, 2021

- Messages

- 282

- Reaction score

- 548

Very interesting, cheers :Y:

A Great Man with a Shovel

By ROBERT KENNEDY

Sitting on the wooden seat on the veranda of the Noondah pub, Jock Macpherson watched a tiny willy-willy frisk itself out of the street dust and spin down the road towards him, to peter- out at the foot of the steps in a flutter of paper scraps. It reminds me of the time, he said, when a willy-willy carried Paddy Dalrymples hat and hung it on the tail of the windmill behind the Diorite pub. None of the heat-weary men on the veranda said anything. Paddy climbed up to get it, Jock went on, but he was always a clumsy cow, he fell off and hit the ground with the grace and ease of a bag of spuds. Even the old Missus, who ran the pub and was known to have a piece of diorite for a heart, was upset as we carried Paddy in. lll get the poor creature a brandy, she said.

lf its all the same to you, Missus, said Paddy, ld as soon have a whisky. So he missed the first free drink offered in Diorite for 40 years. He never could keep his mouth shut and whenever he opened it, he couldnt speak until hed spat his foot out from the time before. One of the men went into the bar and returned with a tray of beer. He was the only visible moving creature in Noondah. Jock took his glass, tasted it, and ran his tongue meditatively along his lips. Well, go on, said the man whod bought the beer. You might be able to make us forget its a hundred and fourteen in the bough-shed. Well (said Jock), this Paddy Dalrymple was one of the best-known men on the West Australian goldfields in the early daysmainly because he did everything wrong. He was an Irishman, as big as a side of beef and somewhat the same color. He had muscles all over him that looked like the Leopold Ranges, and he could shift more dirt with a number-six shovel than any other two men in Kalgoorlie. He had a head of solid bone, which was just as well, because he had no brains inside to stop it collapsing. But that Paddy was a great man with a shovel, my word he was. About 1930, smack in the middle of the depression, he and I were out of Coolgardie, going down Norseman way. We were prospecting about, napping a few reefs here and there, and one afternoon I was specking along a bit of a creek bed, when I picked up a small nugget, not much more than half-an-ounce, but lovely, pure gold. Well, we got the dry-blower to work, and we shook half of Western Australia through it, but not a color did we raise. However, one smoke-oh time I noticed the cap of a reef sticking up about two chains down the gully. I napped a bit off and put it through the dolly-potand up in the dish comes a tail of gold that fairly screams four ounces to the ton. Paddy and I reckon were in.

We sink down on that reef at a speed that wouldnt disgrace these modern Snowy River tunnellers, with visions of paying the storekeeper and retiring to Perth with a roll big enough to buy a pub, maybe. Then, about twenty feet down, with around ten tons of ore on the surface, the reef cut- out as though someone had sliced it off with a knife. We couldnt believe it but it was right enough. Must have been some shift in the formation years ago that left our reef just a pocket of stone sitting by itself. I tell you, our spirits were low that night. You might even say our throats were too tight and dry to talk. A man got up and filled the glasses. Of course (Jock went on), we went down a bit more, and tried driving out a bit to see if we could pick it up, but not a sign. So we took our small parcel in to the battery at Coolgardie and had it put through. We got thirty-five ounces out of the ten tons, which was a help, but we werent in any sound financial state when we stood at the bar of the Denver City that night after the clean-up at the battery.