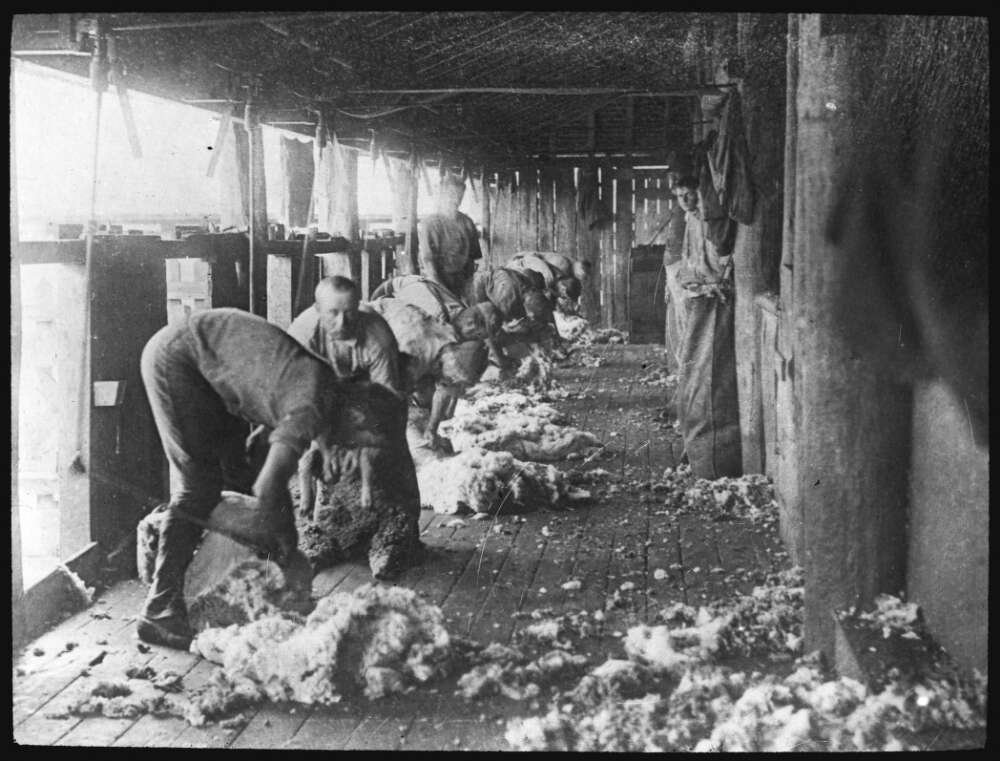

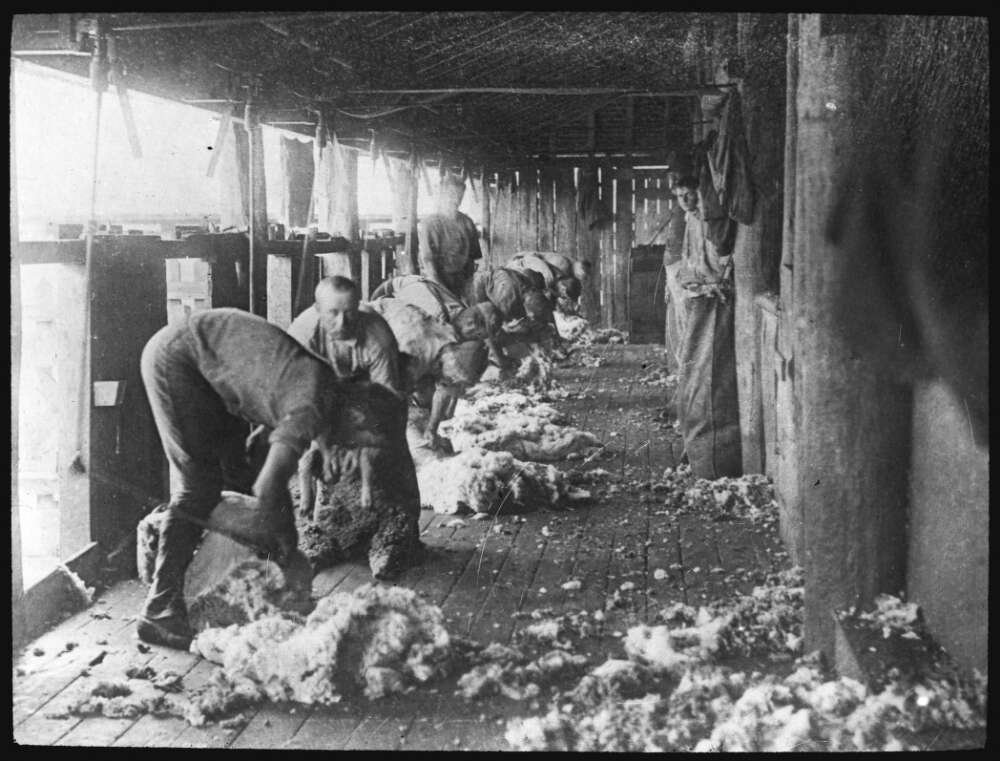

Dutchy refrained from his usual pranks with the rousies; there was no singing at night and gambling, mostly Napoleon, or Nap as it is usually called, was the only form of amusement. As we knew all the station-hands we would go over to the mens hut for a yarn, or visit one of the married mens homes, where we were always sure of a cup of tea and a slice of cake before we went back to the shed huts. The boss of the board, O'Connor, was also the manager of the station. A man with a great idea of his own importance, he was the only boss who ever faulted my shearing. We were shearing six-tooth wethers at the time, and they were fairly rough. I had a look round the other counting-pens and I couldnt see any sheep better shorn than mine. I told OConnor this, and he said: Im the judge of how sheep are shorn here. Never noted for a meek disposition, I replied: You wouldn't know the difference between a sheep and an emu. You probably wish we were back in the days of the raddle stick. He said: I would have used it freely on your sheep. And I said: No doubt, and Id have rammed it down your throat. After this pleasant little discussion, he gave me no further trouble.

Then we got the rain. It came down all night, and the sun was shining in the morning. The sheep that had been under cover were shorn in a couple of hours, and the rousies were jubilant, but not for long. The owners, if they wished, could compel them to work at any job on the station while it was not actually raining. Not many stations took advantage of this clause of the Shed hands Agreement, but Gumin was one of the few. It was really a farce, as none of the men would work. We went for a stroll, and watched a gang who were stick picking. Two men would pick up a branch no bigger than a broom-handle and, pretending to be bowed with the weight, carry it to a heap 100yds. away, while the station ganger stood grinning at them. Half-a dozen would gather round a log that any one of them could lift, and for half-an-hour would discuss ways and means of shifting it. Sometimes one would bend down and grasp the end of the log, grunting and straining to show the impossibility of moving it. Then the ganger would come, hoist it on his shoulder and carry it to a heap, while the rousies commented admiringly on his strength, comparing him with Donald Dinnie, Sandow and other strong men of the time. No matter how little work they did they could not be sacked while on station jobs. After advising them not to work too hard we went to our bunks and slept the afternoon away. It rained every night for a week, and altogether we lost eight days shearing. To several men this lost time meant they would miss-out on their next shed. There were always plenty of shearers to take the place of those who, for some reason or other, failed to turn-up for the roll-call. (Dutchy and I missed Calga, two seasons back, by one hour.) So tempers were frayed, and quarrels were frequent. We managed to avoid getting involved by keeping away from the huts as much as possible. When the last sheep went down the chute everyone was happy, and in two hours every man, shearer or shed-hand, was on his way home or to the nearest pub or another shed.

We went to Box Ridge, a village consisting of a store (which was also post-office), four houses and a dance-hall. No pub. Granny Ingles took in occasional boarders, and we decided to have a week with her and enjoy a bit of home cooking. It may be hard to believe, but for three months, we had not tasted butter, milk or green vegetables of any kind. Such things were never seen in shearers huts or camps; there was no way of keeping them. Our only luxuries were jam or, in a mean shed, treacle or golden - syrup (otherwise cockys joy"). Spuds were the only vegetable, and never too many of them. Granny showed us through the garden, where we swooped on a lettuce each. She reproved us gently: You boys wont be able to eat any tea. Dutchy stopped chewing long enough to say, Who wants any tea? But we did a very good job on the meal she set before us.

Granny Ingles was known and loved by every man, woman and child for 50 miles. The local midwife, she claimed anyone who was under 30 and had been born in the district as one of my babies. I think it was the third day of our stay with her when a worried-looking man, driving a pair of straggly horses, came to Grannys house and said his wife was having a baby. Granny asked a few questions, and then went into action. She took one look at the mans horses, standing with heads drooping and sides heaving; then ordered us to get her own horses in the buggy. In 10 minutes she was on her way to Salty Creek, which was 15 miles away, but rough tracks and dark nights held no terrors for Granny Ingles.

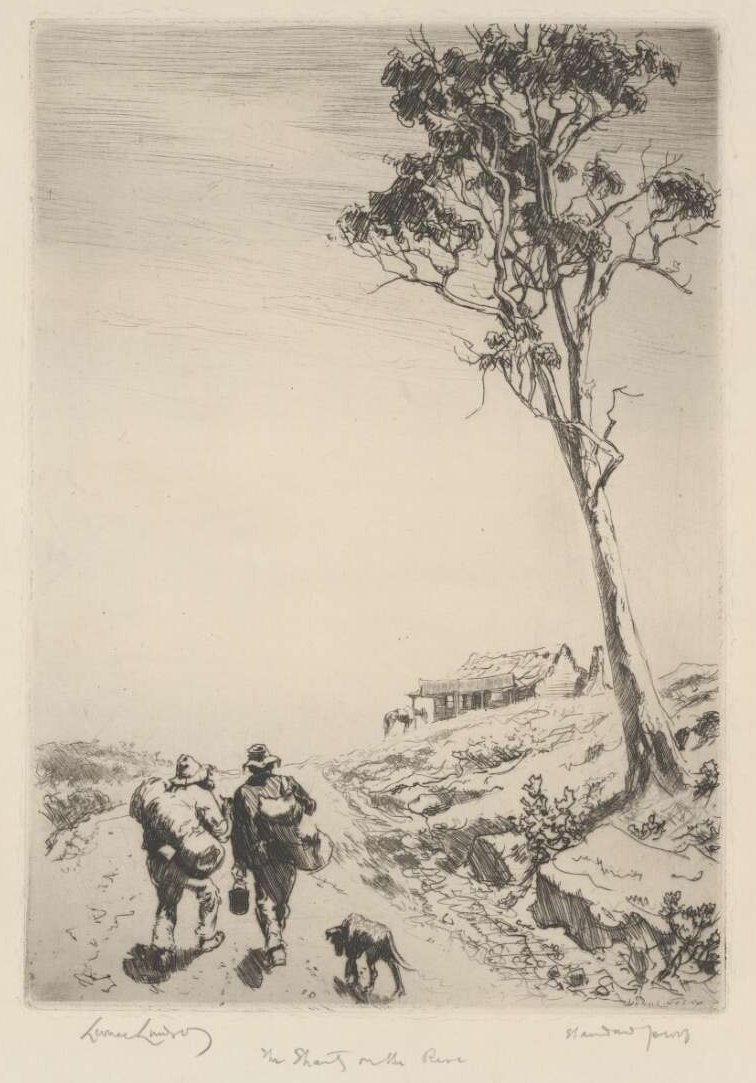

Neither of us slept very well that night. I heard Dutchy turn over and sigh deeply several times. I knew that he was following Granny on that trip, the same as I was. We had offered to accompany her, but she said she would travel faster with less weight. We were asleep when she returned. 1 heard the rattle of pots and pans in the kitchen and took no notice, thinking it was Polly, her daughter, getting breakfast for her brother Billy. He had not been home when Granny had left, but they were not worried about their mothers journey. Polly said: Ive got used to Mums trips. She has been rushing off in a hurry longer than I can remember. But it wasnt Polly in the kitchen. Granny put her head round the doorway, and said in her gentle voice: Dear me, are you boys going to stay in bed all day? We both spoke at once: Is everything all right? She answered: A beautiful girl, and the mother, is quite well. I know I had a lump in my throat, and Dutchys eyes were blinking, and his voice had a queer high note, with a gulp at the end. I drove out with Granny the next day. . The hut was the usual boundary-riders home, just about one class above the aboriginal guny ah. How people lived in them, and reared children, is beyond me.

We had camped at Salty Creek when building the fence between Goorianawa and Gumin, but another family had been living there then. The piesent family had been only six months in occupation. The nearest neighbor, Mrs. Bradley, whom I knew, was looking after the mother. She would drive eight miles to Salty Creek every day, look after Mrs. Sands till the husband came home, which was mostly sun down, then drive back to feed her own brood. Mrs. Sands had four children, besides the new baby. The eldest child was eight. As the baby had been born an hour after Granny arrived, I wondered what Mrs. Sands had been thinking of while her husband was away. Women would know. On the way back I did a lot of thinking, mainly about pioneers. I was really trying to answer my own question: Who are the real pioneers of this country? The women, like Granny Ingles, Mrs. Sands and Mrs. Bradley, will have my vote every time.

We had intended to stay only a week at Box Ridge, but Dutchy had an outbreak of boils, and Granny took charge of him. He was certainly in no condition to go on the track, and I reckoned he was lucky to be in such good hands. The mail-driver from Gulargambone to Baradine wanted a couple of weeks off, so I took the job. The mail coach was one of the famous Cobb and Co.s Probably 20 years old, it was still in good condition. Leather springs, known as through braces, were still used. It rolled, and 1 should imagine the passengers would get seasick on long trips. The original cushions were still in good' order, and 12 passengers could be seated comfortably. I had never driven four-in-hand before, but the horses knew their work, and I had no trouble with them. I picked up the mail at Gular at three in the afternoon, went back to Box Ridge, where I stayed the night, leaving at eight next morning. I dropped mail and parcels at Mount Tenandra and Wingedgeen; changed horses at Goorianawa; then on to Bugaldi and Baradine, reaching there at four. 1 stayed the night; then back to Box Ridge the next day.

The tripGular to Baradine was just 70 miles, and fresh horses were used on alternate trips. I did the journey twice a week, and found it somewhat boring unless I had a few passengers to yarn away the time. Perhaps if there had been bush rangers about to stick me up occasionally it would have been more interesting. Dick Knight, the regular driver, had driven on various runs for Cobb and Co. A little old man, close to 70, he had been driving coaches most of his life. Born in Bathurst, he had known many of the bush rangers well, but had never been bailed-up. He had been a close friend of Johnny Vane, who had died the year before (1906).

Dick told me the story of Jack Skellicorn, who had bet lOO that he could ride from Bathurst to Sydney between sunrise and sunset on the one horse. He completed the ride with an hour to spare, but the other chaps, who had followed him, with several changes of horses, refused to pay because a few times he had dismounted for some purpose or other, and before remounting had led his horse a few yards. Therefore, they argued, he had not ridden the horse all the way to Sydney. A dirty point, but, as Dick remarked, They saved their money, but were the most unpopular men in Bathurst for many years.

Dutchy being well again, and tired of loafing, we took on a fencing-contract for Frank Dowling at Walla, and became members of the employers class. We decided that the ruling wage of 25-bob and tucker for fencing was not enough, so we raised it to 30-bob. Our first man was Ben Bridge, a great worker. He had been to the Boer War, and had been one of Harry Morants Bushveldt Carabineers. Ben had been forced to watch the execution of Morant, and had a fierce hatred of Kitchener, and all British Army officers.

Our second man was Arthur. We were pitching camp when Arthur came along and asked for a job. He was a proper scarecrow tall, gaunt, clothes flapping in the wind, long hair and straggly whiskers. His swag was two wheat-bags tied up with bits of wire and rope. Definitely a bit gone in the head, I thought. Out of pity, I told him he could have a week, to earn a few bob for the track. I reckoned it would be 30-bob wasted. I was wrong. I asked his name, and he said, Arthur. I said, Arthur what? He repeated, Arthur. So I gave up then. It is not considered good form to ask too many questions about a mans name, or to probe into his past too deeply, among bushmen. So Arthur was near enough for us.

We started cutting posts next morning. There was plenty of good timber, mostly cypress pine. Ben worked with me, felling, while Dutchy and Arthur barked the logs and marked-off post lengths. When the first log was ready Arthur grabbed the saw and said, Ill cut em off. He drove the saw through the logs as if they were his personal enemies. Every time it went through he would give a yell of triumph, as though he had won a victory. He was the best single-handed sawyer any of us had ever seen. When he had a dozen lengths ready, he took the hammer and wedges, and started splitting, saying, It does a man good to have a change of work. He used the hammer with the same fury as he had the saw. I thought he would be beat in an hour, but at knock-off time he seemed to be as fit as ever.

Whatever his past might have been, he was certainly a timber-man and a toiler. At the camp he would seldom join the conversation, but would sit for an hour at a time staring at nothing, and his lips moving, as though talking to someone. He had a passion for cleanliness, and some of his rags would be hanging from a tree nearly every night. His age could have been anything from 30 to 50, and he never smoke, drank or swore. Dutchy had a very extensive repertoire of lurid words, and when he was having a session Arthur would shake his head and reprove him gently. And, strange to say, Dutchys language became very moderate when with Arthur. He never worried about Ben or me ; perhaps he thought we were too far gone to bother about.

Ben Bridge is worthy of further mention. Thirty five years of age, ex-soldier, shearer, drover and all-round bushman, he, too, was tireless. 1 fancied myself at putting up posts, but Ben always finished the day with a few ahead. At night he was always ready to sing a songhe had a very good baritone voiceor tell a yarn. He told many stories about his uncle, who was probably the last of the cattle-duffers. When finally arrested and lodged in Blackall (Queensland) Bens uncle had set fire to the jail and escaped, and had never been heard of again.

He had also been concerned with another man when they lifted 3000 sheep from Calga, Goorianawa and Warrina with the intention of droving them to Dubbo and there selling them. They nearly succeeded, but made the same mistake as did Starlight in Robbery Under Arms. On the stock-route near Gulargambone several prize rams joined the flock, and they took them along. These rams belonged to Miss Mary Ferguson, of. Gular station, and had recently been bought from a Victorian stud at a stiff price. A few miles from Dubbo, several buyers came out to inspect the sheep, and the stock-agent who took the prospective buyers out happened to be the man who had bought the rams for Miss Ferguson. He recognised them, and sent for the police. Bens uncle, realising the game was up, went for his life and got clean away. His mate tried to bluff it out, but got three years imprisonment. Ever after, he trod the straight and narrow path, but Bens uncle merely shifted his activities to Queensland, where for several years he was a thorn in the side of many a squatter, till finally yarded at Blackall.

{To be continued )

The bulletin.Vol. 80 No. 4120 (28 Jan 1959)

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-672857150

https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE2348445&mode=browse

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147193023/view?searchTerm=shearing#search/shearing

Then we got the rain. It came down all night, and the sun was shining in the morning. The sheep that had been under cover were shorn in a couple of hours, and the rousies were jubilant, but not for long. The owners, if they wished, could compel them to work at any job on the station while it was not actually raining. Not many stations took advantage of this clause of the Shed hands Agreement, but Gumin was one of the few. It was really a farce, as none of the men would work. We went for a stroll, and watched a gang who were stick picking. Two men would pick up a branch no bigger than a broom-handle and, pretending to be bowed with the weight, carry it to a heap 100yds. away, while the station ganger stood grinning at them. Half-a dozen would gather round a log that any one of them could lift, and for half-an-hour would discuss ways and means of shifting it. Sometimes one would bend down and grasp the end of the log, grunting and straining to show the impossibility of moving it. Then the ganger would come, hoist it on his shoulder and carry it to a heap, while the rousies commented admiringly on his strength, comparing him with Donald Dinnie, Sandow and other strong men of the time. No matter how little work they did they could not be sacked while on station jobs. After advising them not to work too hard we went to our bunks and slept the afternoon away. It rained every night for a week, and altogether we lost eight days shearing. To several men this lost time meant they would miss-out on their next shed. There were always plenty of shearers to take the place of those who, for some reason or other, failed to turn-up for the roll-call. (Dutchy and I missed Calga, two seasons back, by one hour.) So tempers were frayed, and quarrels were frequent. We managed to avoid getting involved by keeping away from the huts as much as possible. When the last sheep went down the chute everyone was happy, and in two hours every man, shearer or shed-hand, was on his way home or to the nearest pub or another shed.

We went to Box Ridge, a village consisting of a store (which was also post-office), four houses and a dance-hall. No pub. Granny Ingles took in occasional boarders, and we decided to have a week with her and enjoy a bit of home cooking. It may be hard to believe, but for three months, we had not tasted butter, milk or green vegetables of any kind. Such things were never seen in shearers huts or camps; there was no way of keeping them. Our only luxuries were jam or, in a mean shed, treacle or golden - syrup (otherwise cockys joy"). Spuds were the only vegetable, and never too many of them. Granny showed us through the garden, where we swooped on a lettuce each. She reproved us gently: You boys wont be able to eat any tea. Dutchy stopped chewing long enough to say, Who wants any tea? But we did a very good job on the meal she set before us.

Granny Ingles was known and loved by every man, woman and child for 50 miles. The local midwife, she claimed anyone who was under 30 and had been born in the district as one of my babies. I think it was the third day of our stay with her when a worried-looking man, driving a pair of straggly horses, came to Grannys house and said his wife was having a baby. Granny asked a few questions, and then went into action. She took one look at the mans horses, standing with heads drooping and sides heaving; then ordered us to get her own horses in the buggy. In 10 minutes she was on her way to Salty Creek, which was 15 miles away, but rough tracks and dark nights held no terrors for Granny Ingles.

Neither of us slept very well that night. I heard Dutchy turn over and sigh deeply several times. I knew that he was following Granny on that trip, the same as I was. We had offered to accompany her, but she said she would travel faster with less weight. We were asleep when she returned. 1 heard the rattle of pots and pans in the kitchen and took no notice, thinking it was Polly, her daughter, getting breakfast for her brother Billy. He had not been home when Granny had left, but they were not worried about their mothers journey. Polly said: Ive got used to Mums trips. She has been rushing off in a hurry longer than I can remember. But it wasnt Polly in the kitchen. Granny put her head round the doorway, and said in her gentle voice: Dear me, are you boys going to stay in bed all day? We both spoke at once: Is everything all right? She answered: A beautiful girl, and the mother, is quite well. I know I had a lump in my throat, and Dutchys eyes were blinking, and his voice had a queer high note, with a gulp at the end. I drove out with Granny the next day. . The hut was the usual boundary-riders home, just about one class above the aboriginal guny ah. How people lived in them, and reared children, is beyond me.

We had camped at Salty Creek when building the fence between Goorianawa and Gumin, but another family had been living there then. The piesent family had been only six months in occupation. The nearest neighbor, Mrs. Bradley, whom I knew, was looking after the mother. She would drive eight miles to Salty Creek every day, look after Mrs. Sands till the husband came home, which was mostly sun down, then drive back to feed her own brood. Mrs. Sands had four children, besides the new baby. The eldest child was eight. As the baby had been born an hour after Granny arrived, I wondered what Mrs. Sands had been thinking of while her husband was away. Women would know. On the way back I did a lot of thinking, mainly about pioneers. I was really trying to answer my own question: Who are the real pioneers of this country? The women, like Granny Ingles, Mrs. Sands and Mrs. Bradley, will have my vote every time.

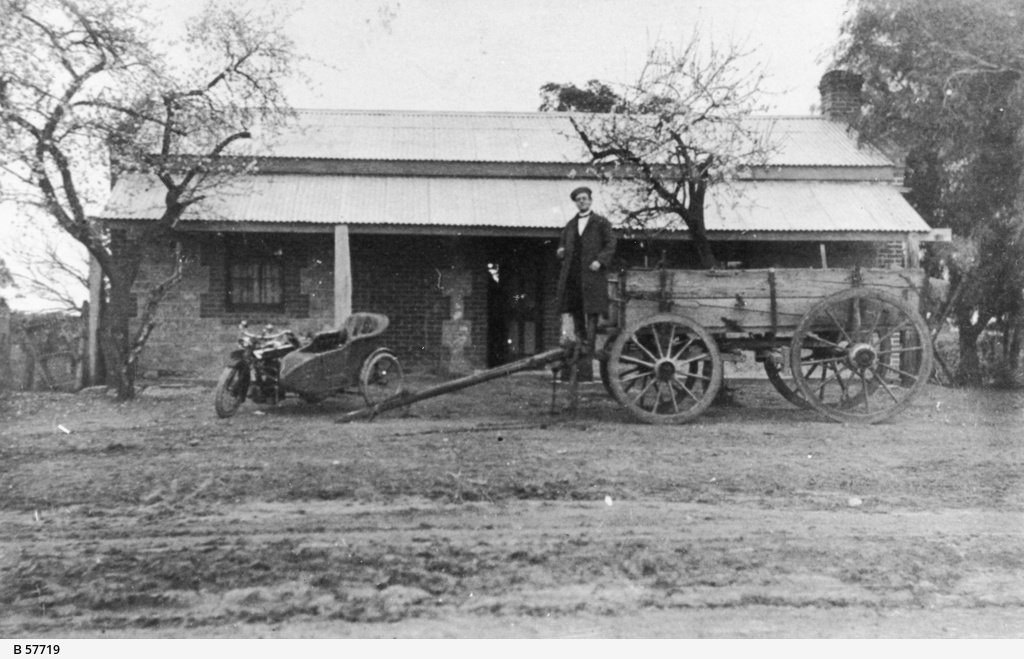

We had intended to stay only a week at Box Ridge, but Dutchy had an outbreak of boils, and Granny took charge of him. He was certainly in no condition to go on the track, and I reckoned he was lucky to be in such good hands. The mail-driver from Gulargambone to Baradine wanted a couple of weeks off, so I took the job. The mail coach was one of the famous Cobb and Co.s Probably 20 years old, it was still in good condition. Leather springs, known as through braces, were still used. It rolled, and 1 should imagine the passengers would get seasick on long trips. The original cushions were still in good' order, and 12 passengers could be seated comfortably. I had never driven four-in-hand before, but the horses knew their work, and I had no trouble with them. I picked up the mail at Gular at three in the afternoon, went back to Box Ridge, where I stayed the night, leaving at eight next morning. I dropped mail and parcels at Mount Tenandra and Wingedgeen; changed horses at Goorianawa; then on to Bugaldi and Baradine, reaching there at four. 1 stayed the night; then back to Box Ridge the next day.

The tripGular to Baradine was just 70 miles, and fresh horses were used on alternate trips. I did the journey twice a week, and found it somewhat boring unless I had a few passengers to yarn away the time. Perhaps if there had been bush rangers about to stick me up occasionally it would have been more interesting. Dick Knight, the regular driver, had driven on various runs for Cobb and Co. A little old man, close to 70, he had been driving coaches most of his life. Born in Bathurst, he had known many of the bush rangers well, but had never been bailed-up. He had been a close friend of Johnny Vane, who had died the year before (1906).

Dick told me the story of Jack Skellicorn, who had bet lOO that he could ride from Bathurst to Sydney between sunrise and sunset on the one horse. He completed the ride with an hour to spare, but the other chaps, who had followed him, with several changes of horses, refused to pay because a few times he had dismounted for some purpose or other, and before remounting had led his horse a few yards. Therefore, they argued, he had not ridden the horse all the way to Sydney. A dirty point, but, as Dick remarked, They saved their money, but were the most unpopular men in Bathurst for many years.

Dutchy being well again, and tired of loafing, we took on a fencing-contract for Frank Dowling at Walla, and became members of the employers class. We decided that the ruling wage of 25-bob and tucker for fencing was not enough, so we raised it to 30-bob. Our first man was Ben Bridge, a great worker. He had been to the Boer War, and had been one of Harry Morants Bushveldt Carabineers. Ben had been forced to watch the execution of Morant, and had a fierce hatred of Kitchener, and all British Army officers.

Our second man was Arthur. We were pitching camp when Arthur came along and asked for a job. He was a proper scarecrow tall, gaunt, clothes flapping in the wind, long hair and straggly whiskers. His swag was two wheat-bags tied up with bits of wire and rope. Definitely a bit gone in the head, I thought. Out of pity, I told him he could have a week, to earn a few bob for the track. I reckoned it would be 30-bob wasted. I was wrong. I asked his name, and he said, Arthur. I said, Arthur what? He repeated, Arthur. So I gave up then. It is not considered good form to ask too many questions about a mans name, or to probe into his past too deeply, among bushmen. So Arthur was near enough for us.

We started cutting posts next morning. There was plenty of good timber, mostly cypress pine. Ben worked with me, felling, while Dutchy and Arthur barked the logs and marked-off post lengths. When the first log was ready Arthur grabbed the saw and said, Ill cut em off. He drove the saw through the logs as if they were his personal enemies. Every time it went through he would give a yell of triumph, as though he had won a victory. He was the best single-handed sawyer any of us had ever seen. When he had a dozen lengths ready, he took the hammer and wedges, and started splitting, saying, It does a man good to have a change of work. He used the hammer with the same fury as he had the saw. I thought he would be beat in an hour, but at knock-off time he seemed to be as fit as ever.

Whatever his past might have been, he was certainly a timber-man and a toiler. At the camp he would seldom join the conversation, but would sit for an hour at a time staring at nothing, and his lips moving, as though talking to someone. He had a passion for cleanliness, and some of his rags would be hanging from a tree nearly every night. His age could have been anything from 30 to 50, and he never smoke, drank or swore. Dutchy had a very extensive repertoire of lurid words, and when he was having a session Arthur would shake his head and reprove him gently. And, strange to say, Dutchys language became very moderate when with Arthur. He never worried about Ben or me ; perhaps he thought we were too far gone to bother about.

Ben Bridge is worthy of further mention. Thirty five years of age, ex-soldier, shearer, drover and all-round bushman, he, too, was tireless. 1 fancied myself at putting up posts, but Ben always finished the day with a few ahead. At night he was always ready to sing a songhe had a very good baritone voiceor tell a yarn. He told many stories about his uncle, who was probably the last of the cattle-duffers. When finally arrested and lodged in Blackall (Queensland) Bens uncle had set fire to the jail and escaped, and had never been heard of again.

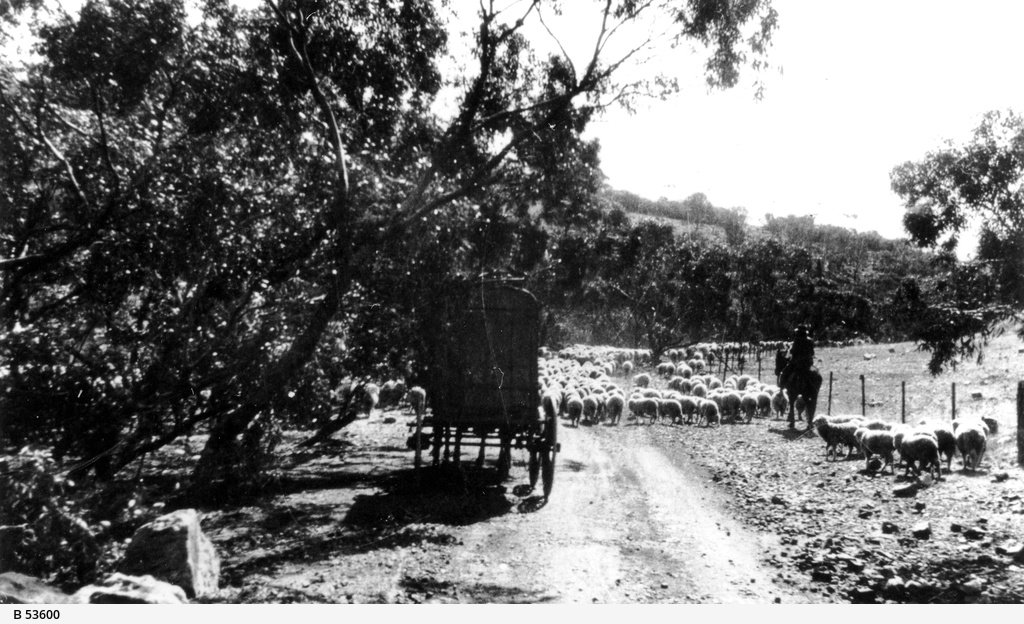

He had also been concerned with another man when they lifted 3000 sheep from Calga, Goorianawa and Warrina with the intention of droving them to Dubbo and there selling them. They nearly succeeded, but made the same mistake as did Starlight in Robbery Under Arms. On the stock-route near Gulargambone several prize rams joined the flock, and they took them along. These rams belonged to Miss Mary Ferguson, of. Gular station, and had recently been bought from a Victorian stud at a stiff price. A few miles from Dubbo, several buyers came out to inspect the sheep, and the stock-agent who took the prospective buyers out happened to be the man who had bought the rams for Miss Ferguson. He recognised them, and sent for the police. Bens uncle, realising the game was up, went for his life and got clean away. His mate tried to bluff it out, but got three years imprisonment. Ever after, he trod the straight and narrow path, but Bens uncle merely shifted his activities to Queensland, where for several years he was a thorn in the side of many a squatter, till finally yarded at Blackall.

{To be continued )

The bulletin.Vol. 80 No. 4120 (28 Jan 1959)

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-672857150

https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE2348445&mode=browse

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147193023/view?searchTerm=shearing#search/shearing