Continued from post #110 Part 4

Time Means Tucker

By H. P. (DUKE) TRITTON

Both o them 19-year-olds, the writer and his mate Dutchy have set out from Sydney in 1905 on a breezily adventurous wander about the N.S.W. outback, learning to become shearers, doing fencing contracts and having a go at gold digging, singing and taking the hat round in the towns, boxing in show-booths, meeting picturesque characters, and generally getting to know the bush and bush folk, and taking life as they find it. They have gone by boat to Newcastle, headed west from there, travelled the country with George Ruenalfs boxing-show, tramped to shearing jobs at big and small stations, and have just had a go at gold-digging on the old Gulgong goldfields.

We rolled our drums, and took to the track once more. Two days late"' we reached Wellington. We thought we could make a few bob singing, but Wellington was noted for a very unpleasant copper. We had gathered a nice crowd, and everything looked rosy, when he came up and gave us an hour to get out of town. The crowd booed him, but we, knowing we would take the rap if a brawl started, gave it away. Parkes was our next town. A nice little town, with tree lined streets and a general appearance of neatness. It, like Gulgong, had been a great goldfield. Our financial position was, as my mate put it, Not broke, but badly bent. He, being a young man of many ideas, suggested we interview the sergeant of police and see if we could get permission to busk in the streets. At the police-station the sergeant listened attentively to our story, looked through a book, then said, Actually, there is no law against singing in the streets, but if you take the hat round it is classed as begging, which is an offence. I think if you put a hat on the ground, and people care to put money in it, that would be in order. However, it lays to my discretion to a certain extent, so if I think your singing is worth while Ill give you the nod, and you can take the hat round. We agreed that his offer was very fair, and for two hours we sang and recited, mainly requests, till we could do no more. The people of Parkes gave generously, and the sergeant, in plain clothes, contributed his share. We reckoned that the police on the whole were not bad chaps. Where we met one tough one, we usually met half-a-dozen good ones. Bogan Gate was a village of about 20 houses, including two pubs. We didnt find any gate, though we had often heard of the man who hung Bogan Gate. Possibly the same bloke who dug the Darling River.

Condobolin, on the Lachlan, was a fair town, and, with police permission, we had a nice collection. From there we went up through Nymagee and Mount Boppy to Cobar. Cobar, though a big town, seemed overshadowed by the huge mullock-heaps of the coppermines. The mines were on the decline, as the lodes were cutting-out, and many of the miners were idle. The general opinion among the men was that the mines had been worked badly. Murdered, said one old Cornishman. The share holders, mostly English, who had never seen the mines, were hungry for quick profits, and ignored the low-grade ore, insisting that only the rich leads be worked. Had they taken the low-grade with the high, Cobar would have been good for a hundred years. The history of mining throughout Australia seems to prove this theory to be true. Rip the guts out, and damn the future, was the slogan for most of the mines in those days. Again the policemen were friendly, and we had two successful nights in Cobar. Then, having an urge to travel the real outback and visit some of the stations made famous during the shearing strikes, we made for Louth, on the Darling. Here we got a job with a drover, taking a mob of sheep to Tilpa, 50 miles down. This took us past Winbar and Compadore. The pub at Compadore had been the scene of many fights during the strikes, so we went there and made a night of it, yarning and singing. I have often regretted being too young at that time to realise the value those stories would be to the historians of today. It is only those I have heard again, years after, that I have been able to recall to my mind.

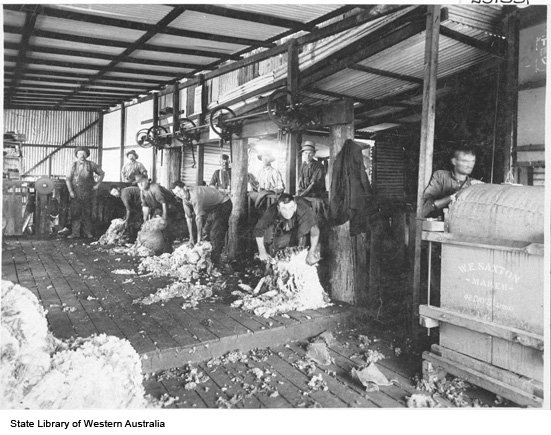

After delivering the sheep at Tilpa, Tommy Vincent, our boss, picked-up another mob to take to Dunlop, on the western side of the river. It was only a two-day trip, but he said he expected to get a lot more work, and as we got on well with him he asked us to go with him. At Dunlop I had a look round the famous shed where shearing-machines were first used in full-scale shearing. The shearers had refused to use them at first, but gradually accepted the newfangled things, which are going to put a lot of men out of work. Also, a lot of time was being lost by the endless-rope (the means of delivering power to the machines) stretching and breaking. One man, an old sailor, had been constantly employed to splice the rope. When the shaft-pulley and friction-wheels were devised, the shearers were satisfied the machines had come to stay. (I met the old sailor, whose only name I heard was Sailor Jack. After a few rums he boasted that he had earned more money than the ringer at Dunlop. He got seven-and-six for each splice, and to be sure of plenty of splices he would cut a strand of the driving rope half-through. Two or three hours later Jacks services would be in demand again, while a mob of cursing shearers stood at their pens, holding half-shorn sheep, or sometimes finishing-off with blades. I remarked to Jack that he was lucky not to be caught at his trick. He laughed and replied, Id have finished-up in the Darling with a coupler dozen machines tied round me neck.)

From Dunlop we took 3000 wethers to Wanaaring, on the Paroo River. Wanaaring had been a big camp during the strike. Nocoleche shed, 10 miles south of the town, had shorn with non-union shearers, and as a result much fighting had ensued. Several attempts to burn the shed had been made, one attempt almost succeeding. Tommy Vincent had no more A droving, so we were on the track again. After those few weeks in the saddle we found padding the hoof a bit tough, but covered the 60 miles to Hungerford in three days.

Henry Lawson mentions Hungerford as a town with a rabbitproof fence, and rabbits on both sides. I agree with Henry that the only feature Hungerford is noted for is the fact that it is situated on the boundary-fence between New South Wales and Queensland. But to me Hungerford always remains clearly fixed in my memory as the place where I first met the Reverend Feetham, afterwards the Bishop of Carpentaria. Feetham was one of a group of young men who had formed a society known as the Bush Brothers, with headquarters at Dubbo. They went hundreds of miles in all directions holding religious services- wherever they could get half-a-dozen people together ; camping with swagmen one night, sharing tucker with them, and dining with a squatter the next night. As all the Bush Brothers were fully ordained, they could marry, christen and bury people. Most of them were Englishmen who had taken Orders, only to find there were no churches for them in the Old Country, so many came to Australia to carry on the job for which they were trained. Around the back country they travelled on horse back, and were always alone.

There were 10 of us camped on the Paroo, and about four oclock we saw a cloud of dust on the road, then a horse and rider came into view, pounding along at a fast canter. The rider saw our camp, and swung off the road. He dismounted and came forward with out stretched hand. Im Feetham, he said, of the Bush Brothers. After shaking hands with the 10 of us, he went on to say: Im holding a service in the town tonight, and Id like to see all you men come along. It doesnt matter what your religion is, just come along and Im sure you will enjoy it. Ill give a short sermon, and well sing a lot of hymns. We promised to go to the service, and he mounted and rode off at a fast rate. A tall, angular man, he rode with arms and legs flapping, in the typical English style. His dress did not improve his appearance on a horse. White pith helmet, coat which seemed too small for him, and baggy riding-breeches stuffed into concertina leggings, made-up an outfit which seemed out of place on the outback tracks. His horse was a huge animal, more of the coaching than saddle-type, built for strength, not speed. But the sincerity and good-fellowship of the man made him loved and respected all over the western districts. His heart and soul were in his work, and many a down-and out swagman had cause to thank him for assistance given when badly needed. He had been known to nurse a man for over a week through a bad bout of the horrors. At the service, which was held in the open, he began with a short prayer, then spoke for 10 minutes in a clear and simple manner on the value of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. He did not ask for converts, nor was there any collection. He suggested Rock of Ages for the first hymn. Then we got a shock, as he was absolutely tone-deaf, and was bliss fully unaware of it. He sang in a loud voice, and halfway through the first verse he was the only singer left. It was impossible to follow him, as there was no rhythm or tune in it, so all present gave-up. This went on through five or six of the best-known hymns, till Dutchy could stand it no longer. He offered to sing Abide With Me, but insisted that he sing solo. Feetham agreed, and Dutchy did a wonderful job. His clear tenor had the crowd fascinated, and they could not help applauding when he finished. Being mercenary-minded, I regretted that I could not take the hat round. Feetham thanked him, spoke for about 10 minutes again, then asked Dutchy to sing Lead Kindly Light. The meeting closed, after a short prayer. Though Feetham had several offers of a nights lodging, he camped with us on the bank of the Paroo. We sat a long time yarning, and he asked many questions about our experiences on the track, and told many stories of his own adventures in the outback. He rode off next morning, with the good wishes of every one, the big horse pounding along in a cloud of red dust. One of the chaps commented: He cant ride, and he cant sing, but hes a damned fine man. With which we all agreed.

To Barringun, along the boundary-fence, was our next trip. The country was arid, sandy soil. Spinifex, a tough grass with every blade a needle-point, and low brigalow scrub were the only vegetation. Every step kicked-up a spurt of fine red dust, which hung in the air behind us. Our clothes and bodies were covered with it, and the flies swarmed in clouds all the time. We had been advised to carry waterbags, and had also filled our billies. But with a water bag in one hand and a billy in the other, we were defenseless against the flies, so the billies were emptied, and with a bunch of twigs constantly waving we managed to keep most of them off. The moment the switching stopped, they settled back like a mask on our faces. At midday we met six camel-teams making for God knows where. Great, lumbering brutes, plodding along, with their large loads swaying. With their queer, rolling gait they looked like prehistoric monsters as they went past in a cloud of dust. They were mangy, slobbering brutes, covered with sores, and swarms of flies. I think camels are the most unlovable animals in the world. Apart from a couple at the zoo, we had never seen them before, and were not impressed

with these, except unfavorably. Their drivers tall, dark, bearded men looked straight ahead, and did not cast a glance in our direction, though we were barely 20ft. from them. I called out, Good-day, mate, to the chap with the leading team, but he didn't answer. I remarked to Dutchy: Friendly lot of blankards, arent they? He replied: Wouldnt like to meet any of them on my own, unless I had a shotgun.

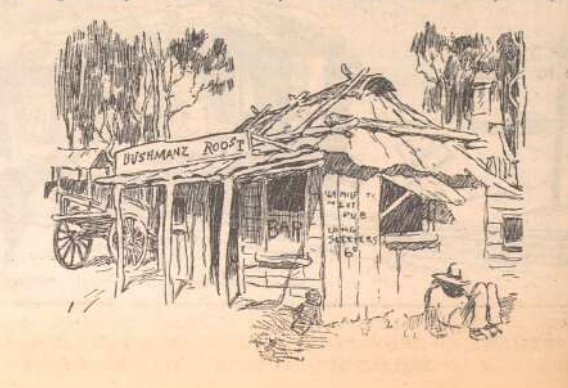

Barringun, on the Warrego River and also on the boundary-fence, like Hunger ford was noted for nothing else except the usual flies, sand, spinifex and brigalow. So, reckoning we had seen enough of the Great Outback, we made for Bourke. The country was very dry, the stock in bad condition, and the squatters unfriendly. One chap whom we asked for rations replied curtly: Not giving any, and if this bloody drought keeps up much longer Ill be on the track myself. Dutchy, in his politest manner, said: Dear me, that would be a calamity! But we had lamb-chops for breakfast next morning. Mid night mutton. This was the country back of Bourke, also known as the land of long leads and short feeds. T'wenty-odd miles from Barringun, Enngonia was noted for its loneliness. The pub, store and post-office were all in one building, which was about the size of the usual boundary-riders hut gable and skillion, with the front veranda closed in to form the bar, and all built of galvanised iron. To enter, one had to duck ones head, and after a few pots of the brew served at Enngonia one was apt to forget to duck. The results were disastrous, and the ensuing language was, to say the least, lurid. There was a police-station, manned by a solitary trooper and a black-tracker. The tracker was picturesque. His uniform was the regular outfit, down to leggings and spurs, but no boots.

There were about a dozen other houses scattered around, but I never found out why people lived there. Enngonia is on the Warrego River, but the river is very hard to find in a dry time, though the locals swore they had seen water in it after heavy rains in Queensland. We were too polite to argue about it. However, if Enngonia had no scenic or architectural features, there was plenty of human interest. Being Saturday, there were men in from all the surrounding stations, with cheques to knock-down, and all seemed eager to be broke again in the shortest possible time. Old men, young men, middle - aged men, bearded, moustached and clean shaven, well-dressed and ragged, all seemed intent on getting drunk. Cheques were passed over the bar, with the words, Tell me when this is cut out, boss.

The bar was crowded-out, and drinks were being passed over heads to the men outside. Invitations to Come an have a drink were heard in all directions. Sheep were being shorn, buckjumpers ridden, dogs, trapped, fences put up, dams sunk, bullocks driven, and all kinds of bush-work was in full swing. Everyone seemed to be talking, but no one listened, except Dutchy and myself. Being swagmen, and broke, we had nothing to talk about. Also, we were waiting our chance to earn a few bob when the drinkers mellowed enough to be interested in listening to our songs. And when the chance finally arrived, and we were going nicely, trouble started.

A character known as Snaky Smith, who was as snakelike as his name suggested, insisted on joining in the singing. As his voice was something like a cross between a dingo and a crow, he was asked to shut-up. But he keep up a running-commentary on our. style, voices and songs, and he was very unflattering. Dutchy walked over to him and asked him to give us a fair go. Snaky answered with a punch, which Dutchy, being a good tradesman, easily avoided, and then calmly proceeded to chop Snaky up. Like most of his kind, he couldnt take it, and in less than two minutes he was a battered wreck on the ground. He was dragged outside, and left to recover. But just as we had the crowd in the right mood to take the hat round, Snaky reappeared with a bottle in his hand. He knocked the bottom out of it, and charged madly at Dutchy. Before he got within striking-distance he was borne down by half-a dozen men, and badly mauled. I reckon he was lucky to escape with his life. The bushman of those days was a great believer in fair play, and if you were unlucky enough to meet a man better than your self, and get a hidingwell, you had to grin and bear it. Bottles as weapons were not looked on with favor, even in a drunken brawl. All the men were in agreement that Snaky had brought the trouble on himself and deserved all he got. But our night was ruined. The trooper and the tracker came over and asked a lot of questions. They had a look at Snaky, then ordered the publican to close up. So the door was shut, and business went on as usual, though no noise was allowed. As we were passing the police-station the next morning the trooper pulled us up and warned us that if we met Snaky in the future to watch him closely. He remarked Its a pity the boys didnt kill him last night. He's a mongrel through and through, and I'd like to get something on him, to put him away for ten years.