The Wraith of Gummy Gale.

LAVERTS pub stood across the gap where the narrow macadamised road swung sharply round an abrupt spur of Wombat Range. On the verandah, in a brown study, sat Davey Brammell, the shearer. His head hung heavy, and he looked like a lost sheep in a strange pad dock. He had knocked down his cheque, and was now getting himself straight again for the track.

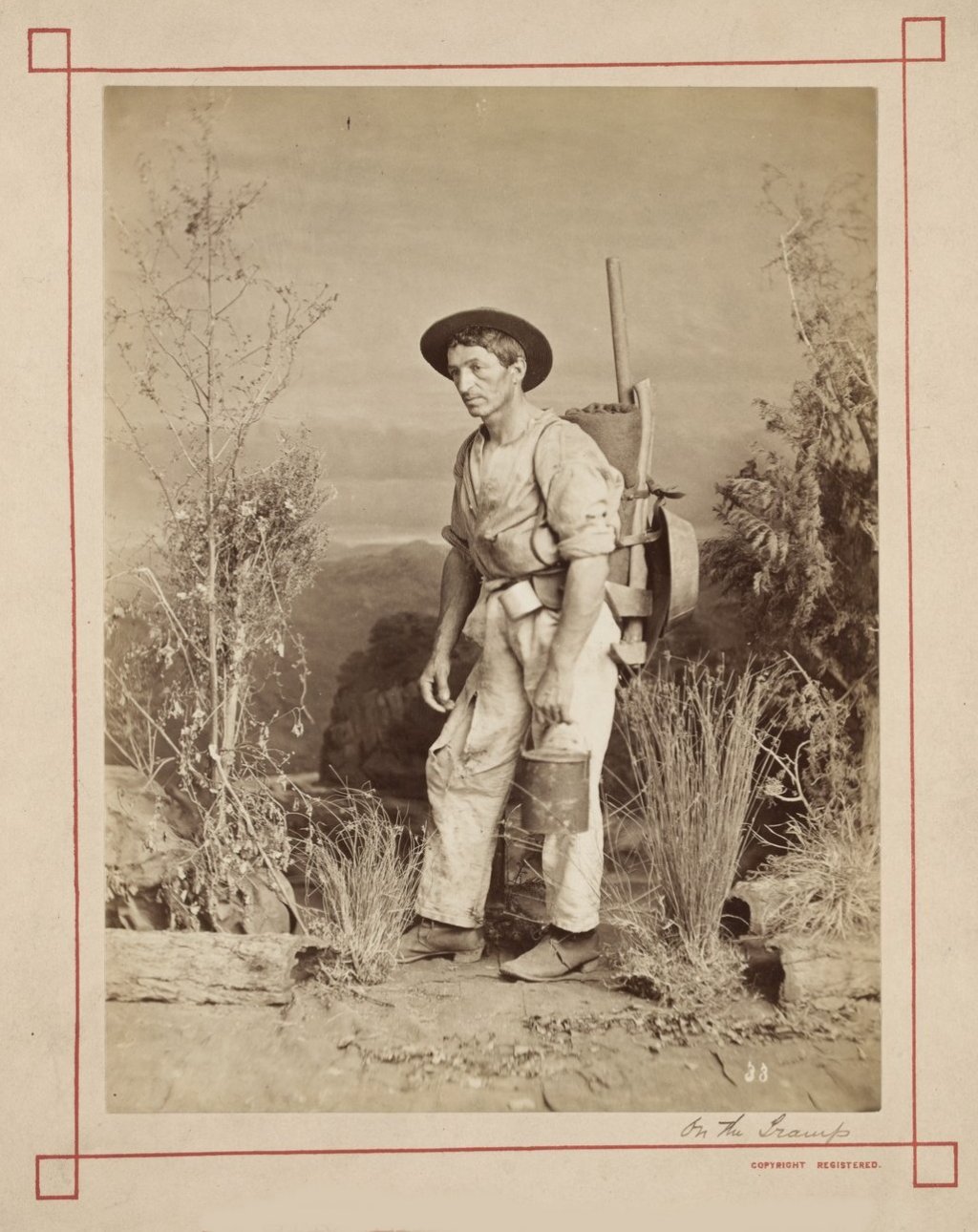

Mick Rooney, an old shed acquaintance, came plodding round the curve, and presently threw his swag down at the corner of the building. Davey was as glad as if Mick had been his own brother. His pot-companions had gone two days ago, and even the bummer had left when he found that Davey was an insolvent proposition. With the exception of some carriers camped a mile down the range, there was not a soul about the place to talk with.

Lavert had been a jolly fellow, always willing for a rubber at euchre, but when Davey had parted his last sprat, Lavert left off playing cards. He also left off talking. So Davey welcomed Mick Rooney. They had a drink, wherefore Lavert raked up a smile and started talking again.

I think Ive seen you before, he said, leaning on the bar and beaming across at the newcomer. Wasnt you pressin at Toonbar one year? I wasme an the Cockroach. Thats a good few year ago now, said Mick, reflectively. You must ave a surprisin good memory.

I dont soon forget faces, Lavert returned. Specially if they owe you a bob or two, added Mick. No one who had once known him could easily forget Mick. He was short and thick set, and wore a big nose dumped in the middle, and a squint in one eye. Davey was a giant beside him; but Davey had a slouching gait and was slow and dull.

I was havin a bit of a yarn with th old girl round th corner, Mick presently resumed, as he thrust his glass back and wiped his mouth with a sweep of his shirt-sleeve. Mother Donefly? queried Lavert. Mick nodded. She tells me Gummy Gale, th hatter, scragged himself in the old hut somewhere about three year ago.

Aye! He went off his onion at the last, an took a drop from the crossbeam. Poor old Gummy! I didnt think hed come ter that. He warnt a bad sort, take him all round. What did he pan out? Tuppence. The yarn goes that he had a pile stowed away somewhere, but I think it was only skite. They found nothing,

anyhowunless it was Mother Donelly. He laughed softly. Did yer ever hear tell of the ghost on the Wombat? he asked. No! said Mick, expectantly. The old woman used to go evry evenin at dusk an squat down on a big rock on the side of the range, Lavert began. Twas just below her place, an overlook in' the caboose where Gale hung out. There she smoked her pipeshe was always fond of her pipe, was Mother Donellyan some times shed jabber to herself for a hour or more. Donelly, yer see, is always away workin on Toonbar; an of course, she feels it a bit lonesome cooped up there by herself. She an Gummy were great friends while he lived. Used ter visit one another reglar. Anyhow, he went off his nanny an took the short cut across the boundary. It was with her dog-chain he done the trick, too.

I remember the barney she had with the bobby to get the chain back. Well, after that it was a common thing to see blokes come peltin round the pint there at night as if the Devil was after em.- Theyd seen Gales ghost. It used to amuse me. Most of em saw him sittin on the rock, smokin, as he used to at his own door, an talkin in sepulchral tones; an some would see him rise up sudden-like, with a deep-drawn sigh, an at times it was a blood-curdlin groan, an glide away like a shadder.

Of course I knew it was Mother Donelly herself, but they wouldnt have it. Not a bit of it. Evry benighted son of a gun that streaked round that corner swore as it was Gales ghost an no other; an the yarn spread about till Wombat Range got sich a bad name that no one but a total stranger would come by there at night. Even the drovers reckon that no mob of cattle can be made ter camp within five miles of it. It got about, you know, that Gale had a bit of stuff planted somewhere by his humpy, an that Mother Donelly got on to it, an so the old chap cant rest, an goes moanin round.

Do you think Gummys swags still buried at th humpy? Davey asked Mick when they were alone out on the verandah. Ill stake me forty years gatherin on it, providin as Mother Donelly aint been an nailed it. She was always a pryin old cat; but, still, Gummy was fly enough for her an he was pretty close-fisted with it. So, all an all considered, it must be there yet. Mick, a haul like that would be a chuck in now ! Davey exclaimed. He straightened his back, with his hands on his knees, and blinked at the road which the dead mans gold might save him from tramping.

Ill tell yer what I was thinkin, Mick went on, with a quick side-glance towards the door. I dont want his bloomin nabs to get wind of it, he added cautiously. Is there such a thing as a pick about, dyer know ? Theres a couple leanin against the horse-yard at th back, said Davey. Theyre not up ter much, but theyll do for what we want.

There was no moon that night, but still it was not very dark. A cloudless sky bedizened with countless stars rendered it an easy matter, for one thing, to pick out the squat form of Mrs. Donefly perched on the rock above Gales humpy. She was smoking, as usual, and enjoying the cool night breeze that came in little puffs along the range. Farther down the slope the carriers fires glowed readily, while the jangle of horse-bells came incessantly from the surrounding timber. Nothing stirred about the building, which stood in the shadow of the hillside. The two men crept towards it, hugging the slope to escape the owl-like eyes of the woman.

The place was in ruins. Many of the slabs had fallen in, leaving huge gaps in the sides; and storm-winds had stripped half the bark from the roof. Davey shuddered as he looked in. He did not like the idea of searching by night for a dead mans gold, however bravely he had spoken of his willingness to do so. Every strange object that caught his eye gave him a shock. He was suffering from the effects of his two weeks spree, and his mind was in a fit condition to conceive a semblance of the uncanny in the most commonplace objects about him. Rooney, though disliking the neighborhood, was intent on business.

They began a systematic search for the misers hoard, starting at the door and working outward with the pick-point, one to the left, the other to the right. Rooney thought the money would be wrapped in cloth or bagging, which would be easily felt with the pick.

Hours they toiled, till the whole surface was broken up for several feet around the humpy. Every boulder in the vicinity was overturned and the ground well probed where it had lain. But nothing was discovered. Looks like huntin for a mares nest, whispered Davey, leaning wearily on his pick.

Dont give in yet, said his mate, though he, too, began to lose hope. Well try in side. I dont like th thought o missin it. They had broken up half the caked floor in their search, when a rustling outside caused Davey to look round sharply.

My Gawd! he gasped the next instant, and the pick dropped from his nerveless hands. Whats up? whispered Mick, Ave yer found it? Look ! Look ! whispered Davey, hoarsely. Wha whats that? Shuffling along the grass was a tall white object that seemed to be sniffing and scratching at the broken ground. It resembled a man lifting himself along on his hams while the rustle of its snow-white garments sounded strangely weird. Even its breathing they could hear deep breathing that made them shudder. The clink of a chain sounded clearly with every movement, and their hair bristled at the recollection that it was with a dog-chain that Gale hanged himself. Suddenly the apparition rose up from the ground and stood waving its white arms as though beating off an invisible foe.

My oath ! gasped Davey, as he clutched the back of Rooneys shirt and goggled across his shoulder. Its Gales ghost! Lemme go, you fool! whispered Rooney, tearing his shirt free and retreating cautiously towards the door. He shook a tottering fist at the outsider. Its arms and body were clothed in a long white robe, and on its head was a fantastic covering that did not look unlike a white frilled bonnet. With trembling knees the treasure-hunters crept to the doorway. Rooneys elbows dug viciously into the other mans ribs, and gripping his pick in his hands he darted from the hut and rushed wildly along the hill. After him, gasping in abject terror, staggered Davey, breathing like the dry pant of a knocked-up dog.

Almost immediately they heard a bump, bump, and the rattle of chains behind them. Lasting terrified glances over their shoulders they saw the Thing flying through the air with a great flutter of white. Now and again it would bump the earth hard, as though gambolling in its glee. Then it would leap into the air again, its arms waving and its white robes flowing. Such peculiar antics demoralised the two fossickers. Their pace dwindled to a tottering walk, and they called on high Heaven to aid them .

As they neared the turn of the road Davey tripped and fell disconnectedly against a bush. The white pursuer flew past him with a jingle of chains that sounded like a death rattle, and the next moment he saw it clutch Mick by the back of the shirt and jerk him to a standstill. Then he knew that clicks soul was demanded of him. A howl came from the victim. He struggled fiercely for a few seconds. Then Davey saw him lift the pick and send it with a wild drive, into his ghostly assailant. He expected to see the weapon clear it as though it were empty air; but it plunked hard and deep into a solid body, and with a lamentable disarrangement of sounds the creature toppled over add lay in a death-agony on the road.

Rooney sank down on the bank, bathed in cold perspiration. Davey, with a new fear gripping his heart, scrambled to his feet and beating wide of the dying phantom, dropped down exhausted. Mick, youve done it! he cried. Done what? panted Mick. Davey groaned in agony. Youve done it, he repeated. Yer spifflicated puffin adder, what ave I done? demanded Mick.

Davey pointed an agitated finger at the unknown. Youve done murder ! Rooney turned cold. You gibberin idiot, what yer say it was a ghost for! he wailed in an agony of remorse. The victims struggles had ceased, and it lay a still white blot on the road. O Gawd, what are we ter do? Youve done murder! Davey reiterated in the tone of one half-demented. Rooney turned on him fiercely. Shut yer fool mouth, yer idiotic gorilla ! he hissed, his squint eye fairly scintillating. Theres only one thing ter doroll up an clear out of this. Get a move on yer, quick ! He hurried down to his camp with the big man panting at his heels Never before had their swags been bundled together and rolled up in such a slipshod manner. In ten minutes, with their boots in their hands, and strips of torn shirt wrapped round their feet to bamboozle the trackers, they were striding across country with their faces set doggedly to the western sky.

Well ave ter travel all night, an spell all day for the fust week. panted Mick, pulling up for a breath after five miles strenuous flight. Davey was too exhausted to speak just then. Must ave been one o them pumplcin-eaded carriers actin th goat, Mick continued, wiping the perspiration from his forehead. But the jiggered thing was flyin! Davey argued. He clutched his swag again, and they went on, onward and westward into the solitudes of the Never-Never, until the phantom police and the spectral trackers were outwitted and beaten.

Towards noon the next day Mrs. Donelly came waddling up to Lavert's. She was mumbling, and when Lavert came out she pointed down the road with her stick. What dyer think o them carriers that cleared out this mornin? she cried with a vicious ring in her voice.

What have they been doin? asked Lavert. She planted the stick hard on the ground before her, and folded her hands on the nob. They killed Barney OBryan larst night, an left him lyin stiff an dead on th road at th pint there. Thats what they did, the dogs! What for? asked Lavert. What for? Mrs. Donelly snorted. Cos theyre a lot o curs. They tuk my white shirt an me own Sunday bonnet off th line an put em on Barney, an then they untied his chain I tied him up at sundown an they tuk him down to the road there an kilt him as dead as a door-nail be drivin a pick through his soul-case. Th dogs, they did!

What ad shame! said Lavert. They want six months. Gaolins too good for th likes o them, Mrs. Donelly declared. They want rollin in a spiked cask down Wombat. Brutes like them, as would steal a lone womans kangaroo for no other reason but to take it away an stoom it out with a pick, ought to be hounded off th roads, so they ought. I want you now, Lavert, to come an help me carry him to th cemetery. Lavert got his hat and they buried Barney OBryan by the side of Gummy Gale.

With the return of the teams they learnt that it was the carriers boys who had dressed Barney and let him go, what time the old woman was having her evening smoke on the rock. But it was not till years afterwards that they learnt how Barney had met his death. The story was told by a harmless crank who had a squint in one eye and a broken nose.

EDWARD S. SORENSON.

The bulletin .Vol. 37 No. 1920 (30 Nov 1916)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/

slab bush hut

https://digital.slq.qld.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?change_lng=en&dps_pid=IE116286